Text: Anna-Liisa Tolonen

”If languages are the key to our cultural heritage…”

”…, then it is necessary to teach them effectively and, if possible, in an appealing way. For this reason the Polis method was developed, turning Polis into one of the very few institutions in the world that teach the so-called dead languages (e.g. Koine Greek, Biblical Hebrew, and Latin) as living languages.” This is the way in w hich the so called ”Polis method” is introduced. But how should one teach “effectively” and “in an appealing way”? And what is meant by the resurrection of ancient languages in contemporary Western academia? This text explores the phenomenon by way of interviewing scholars and teaching faculty connected with the Polis Institute Jerusalem.

hich the so called ”Polis method” is introduced. But how should one teach “effectively” and “in an appealing way”? And what is meant by the resurrection of ancient languages in contemporary Western academia? This text explores the phenomenon by way of interviewing scholars and teaching faculty connected with the Polis Institute Jerusalem.

Professor Christophe Rico’s academic background is in Greek Linguistics. He defended his doctoral thesis on the suffix system of Homeric nouns and adjectives at Sorbonne University in 1992, and he is currently a professor at the University of Strasbourg. For the last twenty years or so, Rico has lived in Jerusalem.

Professor Christophe Rico

Since the early 1990s, Rico has been developing a method of teaching ancient Greek as a living language. An updated edition of his text book Polis: Speaking Ancient Greek as a Living Language (Jerusalem: Polis Institute Press) was published in 2015. Today, Rico is the director of Polis – Jerusalem Institute for Languages and Humanities, which hosts 360 local and international students annually, most of whom come to the institute to learn the languages they want to understand by way of learning to use them.

Why Jerusalem?

– Jerusalem, the city of the Bible, the cradle of monotheism, and the melting pot of the Semitic and Hellenistic heritages, is a unique place in the world for discovering the roots of our civilization through the study of languages. And the Polis Institute Jerusalem is so far the only place in the world where a student can study simultaneously ancient languages (Greek, Latin, Biblical Hebrew and Classical Syriac) and modern ones (modern Hebrew, colloquial and literary Arabic), all as living languages.

– Among many other ones, the Polis method was also inspired by a proven model of language learning: the Israeli Ulpan method for learning Modern Hebrew has enabled hundreds of thousands of recent immigrants to master in record time a language widely considered difficult. This is accomplished through total immersion and the constant involvement of the student in the learning process.

In practice, the Polis Method means that from the first day onward, the teaching and learning of the language takes place in a monolingual environment: the instructor speaks only the language which he/she is teaching and the students ought to do the same. The anticipated outcome is that the student learns the language without an inter-mediating language.

– Through various other teaching techniques (Total Physical Response, TPR Storytelling, conversational pair and small group work, etc.), Polis courses quickly develop functional spoken vocabulary and grammar through constant communicative exchange between the instructor and the students. After two years (four semesters), students can read and understand – not merely decode – simple ancient texts without needing a dictionary. They learn to think in the ancient language and understand it on its own terms, without needing a modern language to stand in between them and the text. From this unique starting point, they may proceed gradually to master the extant literature in their language of choice, Rico explains.

– I have been the first one to benefit from teaching Greek in this way, as the way I learnt to speak that language was precisely by teaching it in a living way. From the moment I started talking Greek, my reading speed in that language increased considerably, as well as the number of texts that I was able to understand without translating them.

Efforts to keep the language in use

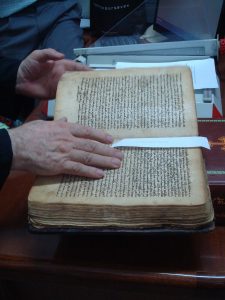

Dr. George Kiraz, Director of Beth Mardutho–The Syriac Institute and Editor-in-Chief of Gorgias Press, teaches ancient Syriac at the Polis Institute, as well as at his own institute in New Jersey. He has also taught Syriac courses at Princeton University, Princeton Theological Seminary and Rutgers University. Kiraz is himself a syriacist, as well as Syriac Orthodox born in Bethlehem. Although Arabic is his native tongue, he regards Suryoyo as his cultural tongue and uses it on a daily basis.

George Kiraz teaches Syriac at Beth Mardutho.

In 1986, Kiraz introduced the Syriac script to the world of computing with his Alaph Beth Computer Systems. As PCs started to become popular, many scholars began to use them. In 1998, Kiraz co-authored the proposal to add Syriac to Unicode which made it possible for Syriac to be implemented in all modern devices and co-developed the Unicode-based Meltho fonts, which has made it possible to have Syriac in mobile devices. Consequently, the Syriac communities, dispersed worldwide, can communicate in Syriac online.

Kiraz is an expert of Kthobonoyo, which is the spoken for of classical Syriac as used in the twentieth and twentyfirst centuries. (For more, see Kiraz’ article ’Kthobonoyo Syriac: Some Observations and Remarks’). As regards classical Syriac, he stresses constant communication with the ancient texts as the only way to maintain high quality of research.

– It is a misconception to think that one can become a good scholar in Syriac after a couple of years of taking courses; immersion in the language takes time and effort. I think it is important for any scholar to become immersed in the language in order to better their scholarly work. Immersion can take two forms: by speaking Kthobonoyo, but also by reading classical texts continuously.

”Dead” languages and their resurrection

Dr. Mercedes Rubio, the Director of Academic Affairs at the Polis Institute, has a background in Medieval Latin and Jewish philosophy (which is mostly written in Arabic, though sometimes with the Hebrew alphabet). She is currently researching the transmission of Aristotles’ texts into the West.

– As I came to work at the Polis Institute, I wanted to experience the Polis method first hand. So I enrolled to a Latin class. You see, although I read Medieval Latin without problems, I could not compose almost anything! The way I had learnt the language never implied that I should use it; instead, I should be able to analyze it by breaking a sentence into pieces.

– In a way, ancient language instructors of the past few centuries have actually killed ancient languages by adopting a way of studying them that mirrors natural sciences, that is by “dissecting” them just as you would do to a frog. This has meant that we do no longer try to understand a text as a whole, as a meaningful unit, but by way of grammatical analysis. Knowing the grammar is essential, of course, but grammatical analysis and translation are but one aspect of the process in which we relate to texts. Languages are first and foremost a vehicle of ideas, of worldviews, and a means of communication. I feel that in a way we have lost this vehicular role of ancient languages and tend to study them as valuable museum pieces, which are out of their natural context.

– I like to think that we are presently witnessing a sort of resurrection of ancient languages, Rico says smiling. – I imagine that within twenty or thirty years, in most Classics and Religious Studies departments, ancient languages will be taught more communicative ways, and we will wonder how people could have done it otherwise before. Further, as more pe ople become able to read ancient texts directly without translation, I expect the quality of research to improve considerably and we will experience a new Renaissance.

ople become able to read ancient texts directly without translation, I expect the quality of research to improve considerably and we will experience a new Renaissance.

Reactions and responses to communicative teaching of ancient languages

José Ángel Domínguez has worked as Director of Language Department at the Polis Institute Jerusalem since its beginning. He also teaches Latin by the Polis method. Domínguez has experienced that immersion in ancient languages may sometimes cause conflicts among proponents of different pedagogical views.

– We are criticized, of course. Wherever I go and talk about the method, I often hear that our approach prevents students from getting to know the grammar. Moreover, using games, for instance, as a resource of learning is considered to be fun for the students but neither serious nor effective. Thus far, our response to such criticism is the results themselves. Student following our method get a deeper knowledge of the structure of the language, not excluding grammar, even if they are capable of understanding texts without constant consultation of a dictionary or grammar. Anyone can take a chance to try how the method works. Moreover, applying the method does not mean that one should abandon other, more traditional forms of teaching ancient languages or disregard the study of grammar; in contrast, the Polis method is open and one may integrate any resource to it that could actively help at finding what we call the “key of the Library of Alexandria”: a more direct access to the ancient sources.

– Our students have, in fact, proven to be a resource for developing the method. We are glad to see that some of our former students have educated themselves to teach Ancient languages as living languages both at our institute and elsewhere. Responding to this, we have started a course on methodology for teachers in Rome every July.

_______________________________________________________________________

Prof. Christophe Rico visits the Faculty of Theology (UH) on Friday, October 21, 2016. The programme of his visit includes a lecture on “The Hellenistic World and its Language,” as well as an introduction to the Polis method. The event is open to everyone (see https://www.facebook.com/events/1786506914950512/); for more information and in order to register, please, contact: anna-liisa.tolonen@helsinki.fi.