by Tero Alstola

After a long siege, Jerusalem fell to the Babylonian forces in 597 BCE. King Jehoiachin and upper classes, the supporters of the rebellion against their Babylonian overlords, were taken captive and deported to Babylonia. The city was plundered, heavy tribute was carried to the temples and palaces of Babylon and a new vassal king was placed on the throne in Jerusalem. Another rebellion ten years later resulted in the collapse of Judean society at the same time, when Judean deportees were resettled in Babylonian towns and countryside. Perhaps a century later, some descendants of these deportees were able to return to Judah and claim a high status in the slowly recovering society.

These events in the sixth and fifth centuries BCE, the so-called Babylonian exile of Judeans, heavily influenced the subsequent development of Jewish religion and literature. Present-day Judaism would look completely different if the exilic experience and trauma had not impacted it. At the same time, the study of the Exile is an excellent example of a research interest that can be thoroughly studied only in collaboration between several academic disciplines: Old Testament studies, Assyriology, archaeology and sociology are all needed. This blog post shows how each of these four disciplines can contribute towards the understanding of the Exile and its repercussions on the development of Judaism.

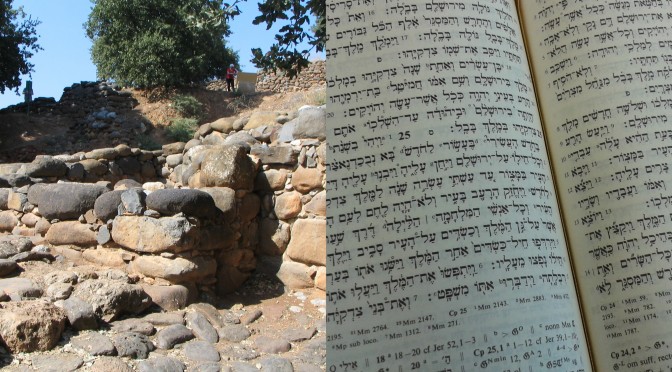

Even though the Hebrew Bible is our main source of information on the events leading to the Exile, the effect of Babylonian military operations on Judah can be properly studied only through archaeological excavations. Their results show how the population of Judah dramatically decreased in the sixth century and the area of Jerusalem suffered heavily from deportations and destruction. This resulted in a long period of diminished population and very slow growth, and only two hundred years later, in the Hellenistic period, significant growth started again. In Babylonia, excavations have unearthed the wealth and glory of Babylon and other cities, but also tens of thousands of clay tablets, which allow us to study Babylonian society in great detail.

Babylonian legal and economic practices produced a wealth of promissory notes, receipts, rental contracts and family documents that sometimes pertain to Judean and other foreign deportees in Babylonia. These clay tablets, written in the Akkadian language using cuneiform signs, are studied by the field of Assyriology. They document the imprisonment of Judean king Jehoiachin in Babylon and the business activities of Judean royal merchants in the city of Sippar. The ups and downs of Judean farmers in the Babylonian countryside are well presented: most farmers had to work hard to cultivate their fields and orchards, pay taxes and make the ends meet, but some of them found business opportunities and prospered by the rivers of Babylon. The Judean exiles were a diverse group, and neither Babylonian sources nor archaeological data bears evidence for large-scale return migrations to Judah.

However, Babylonian sources tell us very little about the religion and culture of the exiled communities and next to nothing about the experience of being exiled. This is where Old Testament studies comes into play. Only the Hebrew Bible and other Jewish writings can reflect the trauma of the Exile and its later impact on the development of Jewish culture and religion. The violent end of the Davidic monarchy in Judah led to a serious theological crisis and the Exile had to be explained somehow. The view that the Exile was a consequence of transgressions against God’s will helped to comprehend and interpret the traumatic events. At the same time, these literary reflections can be better understood when one studies the contemporary exiled and immigrant communities. Sociological and anthropological research can answer to several critical questions: How forced migrations change communities and their internal structures? What strategies are used to cope with the trauma of deportation and exile? What factors affect the decision to stay in the host society or strive for return migration?

One academic discipline alone cannot properly investigate the Babylonian exile of Judeans and one scholar cannot thoroughly master more than one discipline. Only multi-disciplinary work between archaeologists, Assyriologists, biblical scholars and sociologists can shed light on every aspect of this transformational period. In this regard, the humanities can learn a lot from the natural sciences and develop research practices that result in real teamwork instead of loose-knit collaboration between individual projects.

I find it rather interesting that a prolific Jewish writer living in the Egyptian diaspora six centuries after Jerusalem fell, Philo of Alexandria, says nothing at all of the Babylonian exile (nor of the Davidic monarchy). What should we (not) argue from this silence?

Thanks for your comment, Sami!

This is interesting. On the one hand, I would like to think that the diaspora community in Egypt reinterpreted the traditions of the Babylonian exile against their own experience. Even if the miseries of Psalm 137 were foreign to the Jews of Alexandria, the stories about the Jews in the Babylonian and Persian courts (Daniel and Esther) might have been appealing.

On the other hand, I wonder whether the Jews of Alexandria actually associated themselves with the Babylonian exile. Did they feel like living in a foreign place, in contrast to living in Judea?

I think the Alexandrian Jewish community, as long as it existed, was a strong and fairly self-sufficient one. They had their own version of scripture which was not perceived to be in any way second class but expressly equal to the Hebrew original.

Another thing is that the Israelites’ Pentateuchal slavery in Egypt was for Philo a major allegory of the confinement of the soul in the body, and the exodus symbolizes liberation from it. But he nowhere comments on how it feels to be living in Egypt himself — in contrast to the frequent declarations that the body is a foreign land, the heaven (or God), the real home.