We warmly welcome you all to attend the conference “Living Communities and Their Archaeologies: From the Middle East to the Nordic countries” at the University of Helsinki on Thu 12 and Fri 13 September 2019.

You can REGISTER HERE (open until 5 sept) and find more information about the conference and its programme.

Conference venue: Athena 166 (Thu) and 167 (Fri), Siltavuorenpenger 3A, Helsinki. (Note that we have only limited seating available at the conference venue.)

The field of community archaeology has been growing for several decades and has been explored in many countries across the world, including countries in Northern Europe and the Middle East. One of the issues that has sprung up in this research and practice has been the fundamental issue of what we understand as “community archaeology”. This seemingly simple question refers both to the “communities” and the “archaeologies” concerned, and to the interrelations between them. Which communities are we addressing when doing community archaeology (and which are ignored)? What approaches to archaeology do we employ? Is it only excavation, does community archaeology end when the excavation season is over? How do we affect the community in which (or with which) we work? How does the community affect us, the archaeologists? And how can we measure and explain success or failure of “community archaeology” projects?

We are very happy to have as keynote speakers: Dr. Shatha Abu Khafajah (Hashemite University, Zarqa), Dr. Tawfiq Da’adli (The Hebrew University of Jerusalem), Dr. Paula Kouki (City of Hamina / University of Helsinki), and Dr. Gabriel Moshenska (University College London).

- Complete programme: https://www.helsinki.fi/en/conferences/living-communities-and-their-archaeologies/programme

- Practical Information & Social Media guidelines: https://www.helsinki.fi/en/conferences/living-communities-and-their-archaeologies/practical-information

The conference is sponsored by the Centre of Excellence in Ancient Near Eastern Empires (www.helsinki.fi/anee) and the Centre of Excellence in Changes in Sacred Texts and Traditions (www.cstt.fi)

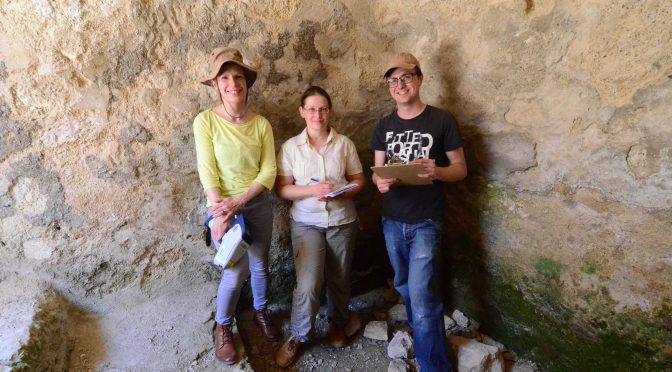

(Photo courtesy of Gideon Sulimani)