By Timo Tekoniemi.

What do Han Solo and King Solomon have in common? How about the many deleted scenes of the first Star Wars film A New Hope, and Yahweh’s consort Asherah? Certainly no association can be made between George Lucas and the genesis of the ancient sectarian Qumran community?

Despite over two millennia separating these characters and texts, these phenomena are indeed linked to one another. Not only has it been often noted that Star Wars fandom resembles in many respects a religion of its own, but both the Hebrew Bible and modern films are shaped and revised by editors, who are also bound to use similar editorial techniques. Like the ancient scribes, professional film editors have omissions, transpositions, harmonizations, and even theological/ideological corrections in their toolbox. In this light, one immediately recognizes the similarities between the many omissions made to the very first preliminary cut of A New Hope (“The Lost Cut”), which was deemed as a failure and in need of radical re-editing, and the likely omission of the Israelite goddess Asherah from the Hebrew Bible. Both of these radical and vast omissions were made necessary in their respective new contexts, whether a need for a watchable movie or a new theological paradigm where Yahweh was understood as the sole god of the Israelites.

The editorial interventions of scribes and editors were/are not always this drastic, however, but, more often than not, rather small and slight – but far from inconsequential. For example, when we note that in the Septuagint edition of 1 Kings 11:1 King Solomon seems to become less sinful, being simply a “lover of women” instead of “lover of foreign women” (thus breaking against Deut 7:1–4, where intermarrying with foreigners is prohibited), we are likely dealing with a slight ideological enhancement of the picture of the pious king Solomon. This impression is corroborated by a similar “pious correction” later made by George Lucas to his re-edited Special Edition (1997) of A New Hope. Despite being the only one to shoot in the original version of the film, in the now infamous scene of the Special Edition one of the heroes, Han Solo, seems to shoot in self-defence only after the bounty hunter Greedo, who is after the reward on his head. This change mitigates the blame of Han’s cold-blooded murder – and, in fact, renders Han a victim of Greedo’s aggression!

Despite its minor scale, this alteration made by Lucas has incited widespread opposition in the fan community, as it considerably changes the depiction of Han Solo, and has therefore larger ideological repercussions to the whole saga. Thus, when the fans maintain to this day that “Han shot first”, they are in fact defending both their right to claim authority to maintain their view of the old canon (where Han still shoots first) and the earlier, untampered textual edition, the original trilogy. There is an ongoing battle between the different Star Wars canons, which forms a very close parallel to the current scholarly dispute concerning the canonicity of different books and editions of the biblical books. It is likely that observations of this ongoing modern “battle of canons” could also help biblical scholars to better understand how the ancient communities (and their leaders) may have understood and contested the different ideas of textual canon(s) of their time.

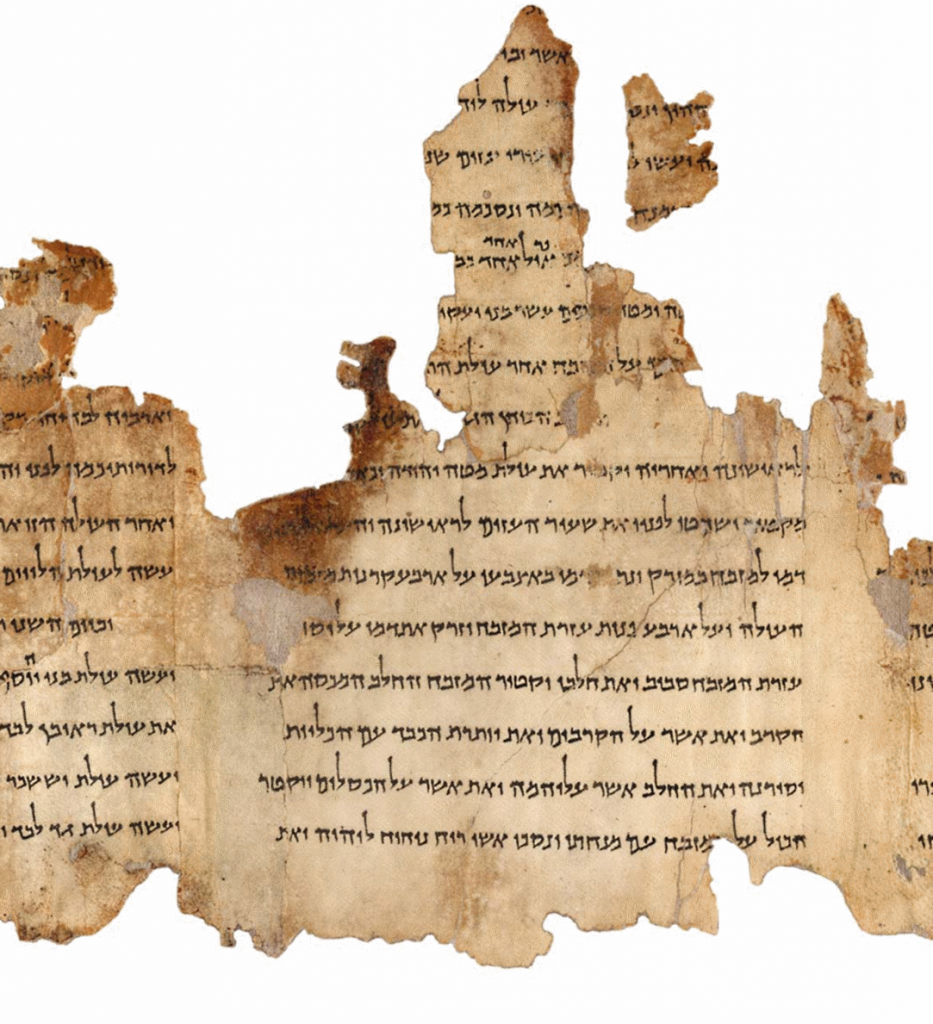

Like the Qumran community, which seems to have severed its ties with the Jerusalem priesthood after some theological disagreements, also parts of the fan community have gone as far as completely denouncing George Lucas as the “high priest” of the saga. To them, Lucas no more has any authority in matters concerning Star Wars. Many of these fans have taken matters in their own hands in the form of fan-editing, i.e. editing the movies themselves to better conform to their own canonical picture of the saga, which is mainly based on the original trilogy. In the process these fan-editors have created a fluid and massive textual plurality of different versions and editions of the loved Star Wars movies (to date at least 137 fan edits!). Somewhat paradoxically, however, the fan-editors see themselves not as rebellious renegades, but, on the contrary, as the keepers of the flame for “the original Star Wars,” now seemingly desecrated and abandoned by Lucas. This massive interpretive textual plurality resembles in many ways that found in the caves of Qumran.

It has become clear that there are multiple parallels between the Star Wars saga, its editing, and its reception by the fan community, on one hand, and the editing of the Hebrew Bible, on the other. Viewpoints taken from Film Studies are therefore not only valid when assessing the editorial techniques reflected by the Hebrew Bible, but might, with further research, prove to be an invaluable parallel and aid to text- and literary critics alike, enhancing our understanding of the textual evolution of the Hebrew Bible. Since the Star Wars franchise is also currently in a textually active situation, with new instalments being filmed at the very moment (the next film, focused on young Han Solo, will be published in May), the saga is an excellent example of a constantly evolving literary work.

Texts were and are thus rewritten exactly because of – not in spite of – their importance to the community. Even radical editing of a text is, at least to a certain degree, always a means to preserve an earlier text that is perceived as somehow important. An immutable text becomes, in a way, dead, and in danger of being simply forgotten; or, in the words of George Lucas, “films never get finished, they get abandoned.”

Timo Tekoniemi’s article “Editorial In(ter)ventions: Comparing the Editorial Processes of the Hebrew Bible and the Star Wars Saga,” was published in the Journal of Religion & Film 22/1 (2018): 1–30. It can be downloaded either at the journal’s home page or his academia.edu page.