by Tero Alstola

This blog post is a summary of Tero Alstola’s recent article “Judean Merchants in Babylonia and Their Participation in Long-Distance Trade” in Die Welt des Orients 47 (2017), pp. 25–51. https://doi.org/10.13109/wdor.2017.47.1.25.

The Babylonian exile of Judeans does not equal to enslavement and miserable conditions in a foreign land. The available sources attest to remarkable diversity within the deported population: although the majority of Judeans worked as small farmers, some of them lived in cities, enjoyed a good socio-economic status, and were integrated into Babylonian society. Judean merchants are an example of exiles who did relatively well in Babylonia.

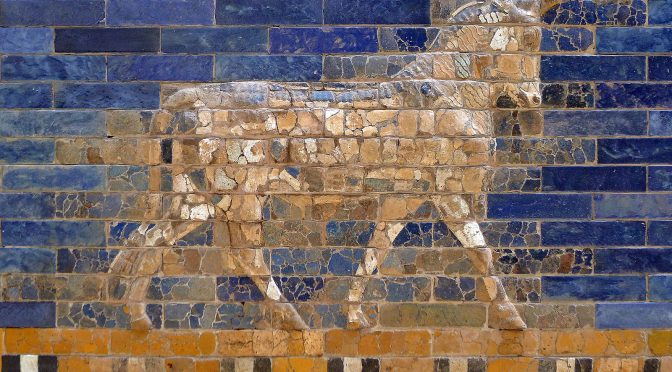

Migration was a common phenomenon already 2,500 years ago. It directly contributed to the development of Judaism and the Hebrew Bible, as the forced resettlement of people from Judah to Babylonia ignited a process of theological reflection among the exiles and their descendants. The Hebrew Bible, however, sheds little light on Judean existence in Babylonia, but documents written in Babylonian cuneiform script inform us about the everyday lives of the exiled Judeans. This blog post focuses on a number of Judean merchants active in Babylonia in the sixth century BCE.

Due to the nature of their business, Judean merchants were more deeply integrated into Babylonian society than their compatriots who worked as farmers in the Babylonian countryside. A family of Judean royal merchants, the children and grandchildren of a certain Arih, lived and worked in the city of Sippar. Royal merchants were people who worked in the service of the crown, engaged in trade, and invested royal funds in commercial activities. The descendants of Arih belonged to the Sipparean trading community and managed to marry their daughter to an established Babylonian family. Such intimate contacts with Babylonians are rare among the Judean population in Babylonia, and they suggest that the family’s profession and privileged status as royal merchants facilitated their integration into local society.

Travelling and the transportation of goods are an integral part of commercial activity, and Judean merchants were involved in long-distance trade outside Babylonia proper. The descendants of Arih traded with a local temple in Sippar selling gold to the temple on one occasion. As gold was a luxury good which had to be imported to Babylonia, these Judean traders at least knew people who embarked on trading missions outside Babylonia. Moreover, our sources attest to other Judeans whose involvement in long-distance trade is fairly certain.

Sources on Judean merchants in Babylonia highlight the diversity among Judean exiles in Babylonia. Although the majority of deportees cultivated land in the countryside, some Judeans managed to secure a higher socio-economic status. Trading was an international activity and was open to merchants of non-Babylonian origin. The same applies to the royal administration, which did not only rely on native Babylonians and Babylonian cuneiform script, but the Aramaic language and people of foreign origin played an important role in it. Judean royal merchants in Sippar are an example of these features of Babylonian society in the sixth century BCE.

Because Babylonia had only few natural resources, the majority of luxury items had to be imported. Merchants of foreign origin, including Judeans, were involved in long-distance trade between Babylonia proper and other parts of the Near East. The travels of Judean merchants reached the territory of modern Iran, and it is possible – but cannot be proven – that Judean traders also had contacts with regions to the west of Babylonia. Such contacts might have provided a communication channel between the Judean communities in Judah and Babylonia.