Authors: Nea Ketola, Pauli Putkiranta, Aarni Vaittinen, Ruben van Baare (from the course ECGS-036, Arctic and Human Beings)

What will be lost as climate change alters ecosystems in the future? No one knows the full answer to this question. Some insight into future changes can be gained by studying “early warning” ecosystems, which are especially sensitive to changing climatic conditions. One is the subarctic palsa mire.

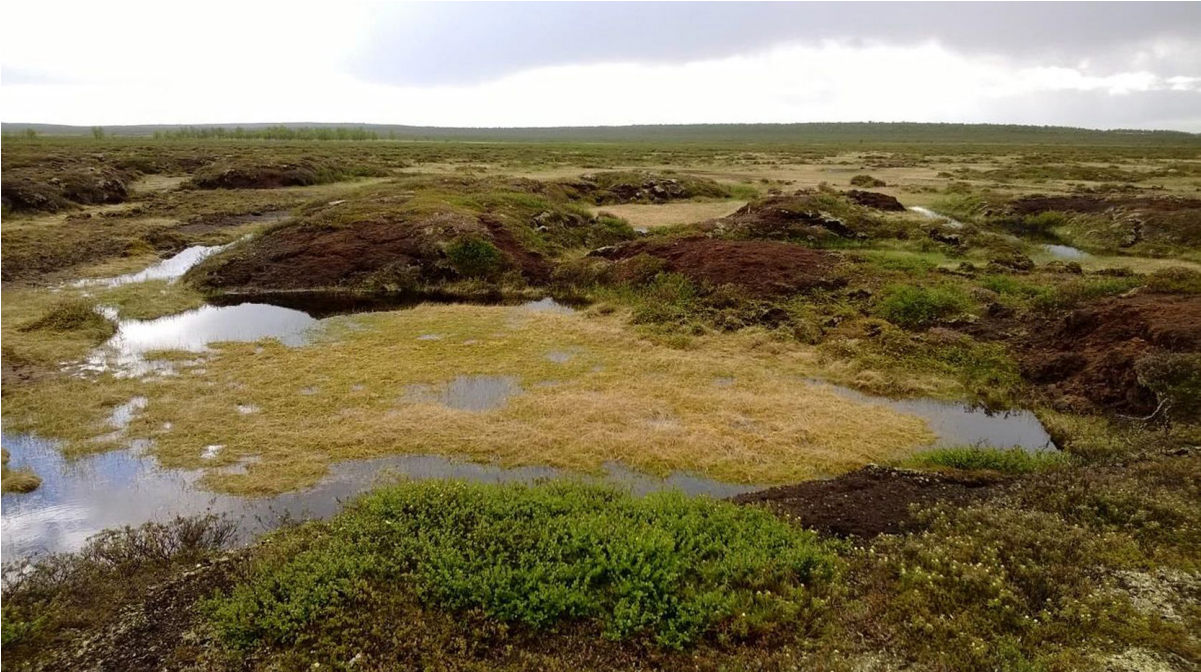

Palsa mires are mire complexes containing peat hummocks with permafrost cores, called palsas. They are found at the edges of the continuous permafrost zone in Fennoscandia, Russia, Canada, and Alaska.

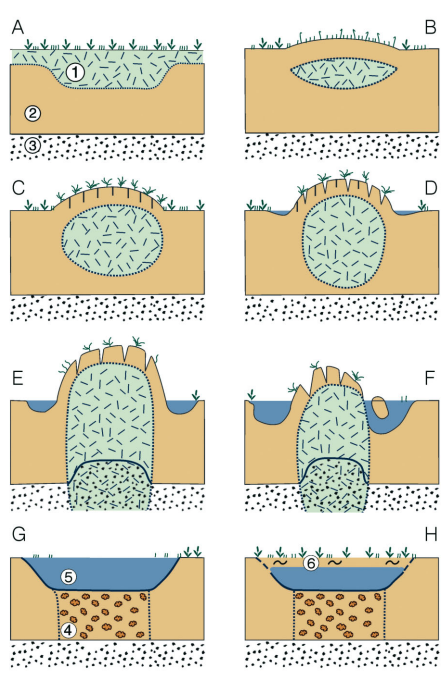

Palsa formation is a cyclic process. In certain parts of the mire, winter frost penetrates deep enough to remain frozen in summer. The remaining frost core increases in size during following winters, raising the surface above it and forming a mound, the palsa. Eventually it starts to degrade and collapses into a puddle of water. Palsa mires are therefore heterogeneous landscapes consisting of palsas in various life cycle stages.

Palsas require specific climatic conditions to be sustained, as the insulating peat layer around the frozen core needs to stay dry and cold enough to prevent thaw. Currently, rising temperatures and increasing rainfall are causing palsas to degrade rapidly, and new palsas are not forming at the same rate. Current models predict that all palsa mires in Fennoscandia could be lost by the end of this century.

Birds love palsa mires

The stages of the palsa life cycle provide diverse habitat services, most notably for birds. Many migratory bird species favour palsa mires, where open water provides abundant food (mainly insects) and nesting sites. Wader and passerine species are particularly abundant. Though most palsa mire species are not globally of conservation concern, many are locally threatened according to Finnish data and global populations are typically declining. A dramatic example is Anthus cervinus, which is critically endangered in Finland, vulnerable in Sweden, yet of least concern globally while still declining. More moderately, Phalaropus lobatus is vulnerable in Finland while global population levels are yet steady and of least concern.

Nonetheless, local declines in areas where suitable habitats are disappearing can provide a glimpse into grimmer futures more broadly. While declining species are not ones that have clear direct social consequences, as they are not traditionally hunted or otherwise harvested, ecological changes have the potential to cascade through trophic systems in unpredictable ways, with unpredictable and potentially far-reaching consequences. For example, Arctic insect populations face diverse population changes, where rare specialist species may be disappearing in favour of common generalists. Vulnerability under changing weather, such as repeated thaw and freeze in spring, may further homogenise insect populations, destabilising the food sources of mire bird species. Under such conditions, single events may push species or trophic systems over thresholds, resulting in, for example, loss of pollination services and prey animals for Arctic foxes, an overabundance of mosquitoes, or just an eerie silence reminiscent of the DDT-induced devastation described by Rachel Carson.

The future of palsa mires

Palsa mires are expected to lose their characteristic heterogeneity, and transform into increasingly uniform and wet landscapes. This could have severe impacts on the environment and the ecosystem services provided by palsa mires, such as the previously discussed bird habitat function. The shallow puddles are expected to expand when palsas collapse, which could improve food availability for birds. This will also affect vegetation, for example cloudberries (Rubus chamaemorus), which are an abundant species in palsa mires and a culturally important food source for locals. The vegetation shift will increase carbon fixation, but this may be negated by increased methane emissions from permafrost thaw.

As palsa mires disappear, the unfolding landscape can foreshadow broader ecological changes in the Arctic. It is likely that some other forms of wetlands will also disappear and become more homogenous. Over time, this could result in a landscape that does not provide the necessary conditions for birds and berries, and will provide less ecosystem services to humans.

Not just birds and berries at risk

While we have focused here on the habitat services currently provided by palsa mires, the consequences of their ever-more-likely demise extend across sectors. In addition to being optimal bird watching sites, the loss of palsa mires will have an effect on habitat services for birds and berries. Furthermore, their degradation alters mire topography, vegetation structure, hydrological processes, and biochemical cycles. There are also societal impacts for local communities. Provisioning services for humans and reindeer will likely diminish as growing conditions for terrestrial vegetation deteriorate. This could result in yet another stressor for reindeer herders, who are already struggling to cope with changes in Arctic environments. Finally, palsa mires are large carbon stores — not to mention the fact that they are a unique geomorphological phenomenon and a characteristic feature of the Fennoscandian Arctic.

All these functions are at risk of being lost. As palsa mires are among the first ecosystems to disappear, we may witness a possible future for many Arctic landscape features, all of which provide crucial ecosystem services. The prospect of these losses should be faced with clarity, even while acknowledging that uncertainty is the name of the game every step of the way. And while these strangely beautiful Arctic landscapes may have seemed distant and irrelevant before, we hope this text has proven the opposite: palsa mires are not to be forgotten.