Authors: Jenni Sohlman, Margaret Mullen, Paul Wittke, Tatu Leppänen & Zélie Jodogne-Del Litto (from the course ECGS-036 Arctic and Human Beings)

Even though we know that there likely is a plethora of resources that could be excavated from the High Arctic, economic activity in the region remains low for a multitude of reasons. Early in the 20th century, national interest in Arctic hydrocarbons started to intensify. Particularly in the second part of the century, major oil fields were discovered, and extraction began to take place. Still, after promising estimations in 2008 about the quantity of hydrocarbons in the Arctic, it seems that the discovery and extraction of new hydrocarbons has slowed down increasingly. When it comes to minerals of the High Arctic, the exploration and efforts made for extraction are still way behind the ones for hydrocarbons, and there are significant reasons for the tardiness of the development.

Why is it then, that these High Arctic resources are not brought more into focus?

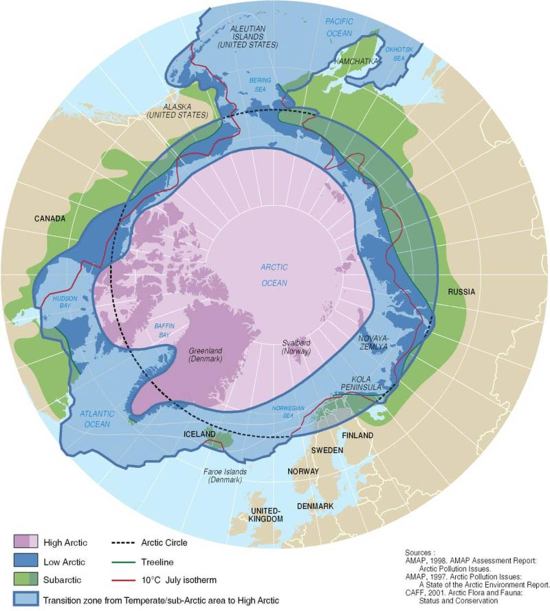

Rekacewicz, P. 2005. UNEP/GRID-Arendal. Vitalic Arctic Graphics. https://www.grida.no/resources/7010

Exploration and perception of High Arctic resources

Fueled by the discovery of major oil fields on the coast of Alaska and the Soviet Union in the 1960s, the exploration of the Arctic for natural resources intensified. Now and then interrupted by ecological concerns, exacerbated by environmental disasters like the Exxon Valdez Oil spill in 1989, more and more resources, specifically hydrocarbons, were detected and extracted. However, most of these extraction operations took place onshore, or at least close to the coast, where the conditions were similar to ones already known of. Until today only two extraction sites are considered Arctic: the Snøhvit gas field north of Norway and the Prirazlomnava oil field in the Pechora Sea near Russia. They started extracting in 2007 and 2014 respectively, almost 20 years later than they were discovered.

Since then, oil companies have pushed further north, beyond the boundaries of the High Arctic, as they have invested billions of dollars in surveying and purchasing commercial rights to potential hydrocarbon reserves in the region. Despite this, most companies have not acquired any profitable extraction sites. Just recently Greenland’s government announced the end of new oil and gas exploration on the state territory; instead they claimed the future would lie in renewable energies. While large reserves of hydrocarbons do exist in the High Arctic, the complex and dangerous extraction methods required in the region do not make extraction worthwhile. The demand for hydrocarbon resources, and subsequently its market value, would have to skyrocket for Arctic extraction to become economically viable. Even if this demand existed, the infrastructure for drilling would not be in place for years. Despite this, most companies continue to invest in High Arctic oil licenses as a means to keep their foot in the door. Allegations that the High Arctic houses the last frontier of carbon resources do not hold true under the reality that these hydrocarbon reserves remain almost unattainable and somewhat undesired in the current climate of oil demand.

Considering mineral resources on the ocean floor, as the field of deep-sea mining evolves, the High Arctic doesn’t seem to be the primary target for extraction. The majority of Arctic mineral deposits are found on land, most of them being located in Greenland, discovered from expeditions made during the 20th century.

In the 1990s, some mineral sites were discovered on ridges in the High Arctic Ocean. It all started out with the unique geological environment of the Iceland crust and with the discovery of gold deposits. Aside from gold, several hydrothermal vents were discovered, which led to the systematic mineral mapping from Northern Iceland up to the Aurora Hydrothermal Vents Site in the North-Eastern coast of Greenland.

Going further north, the presence of hydrothermal vents has also been confirmed in the Gakkel Ridge, also known as Arctic Mid-Oceanic Ridge, and in general sulphide deposits are associated with these vents. The High Arctic exploration though has been done primarily for motives stemming from biological research. Apart from cheaper base metals, such as copper, the more precious ones associated with these vent output accumulations include for example cobalt, gold, molybdenum, platinum and silver. Quantities and profitability of extraction is another question, as well as the environmental consideration of these sites including the partially novel species associated with them.

Relative importance and unknown future

Considering the uncertainties and extraction related factors discussed above, the future is difficult to predict. Apart from the previously discussed variables, climate change also hugely affects the likeliness of possible scenarios, considering the economic utilization of High Arctic resources.

When it comes to hydrocarbons, it is probable that companies keep an eye on the environmental, geopolitical and technological development in the High Arctic, as well as the market situation. However, right now the interaction of these three does not, and in the near future will likely not, create incentives big enough to justify action in the region.

If High Arctic oceanic mineral extraction is considered, next to the uncertain quantities of metals likely to be found, the life associated with the hydrothermal vent sites counterweighs the motives for furthering the effort to some extent. Overall deep-sea mining is still a novel field, with a primary focus on more studied and more easily reachable sites, as the environmental conservation practices are still under development among other factors.

Authors: Jenni Sohlman, Margaret Mullen, Paul Wittke, Tatu Leppänen & Zélie Jodogne-Del Litto (from the course ECGS-036 Arctic and Human Beings)

All authors are Master-level students at the Environmental Change and Global Sustainability program (ECGS), University of Helsinki

References and further reading

Boschen, R.E., Rowden, A.A., Clark, M.R. & Gardner, J.P.A. 2013. Mining of deep-sea seafloor massive sulfides: A review of the deposits, their benthic communities, impacts from mining, regulatory frameworks and management strategies. Ocean & Coastal Management 84:54-67.

Ermida, G. (2014). Strategic decisions of international oil companies: Arctic versus other regions. Energy Strategy Reviews, 2(3-4), 265–272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esr.2013.11.004

Ramirez-Llodra, E., Argentino, C., Baker, M., Boetius, A., Costa, C. et al. Hot Vents Beneath an Icy Ocean: The Aurora Vent Field, Gakkel Ridge, Revealed. Oceanography, 2023, 36 (1), ff10.5670/oceanog.2023.103ff. ffhal-03876877