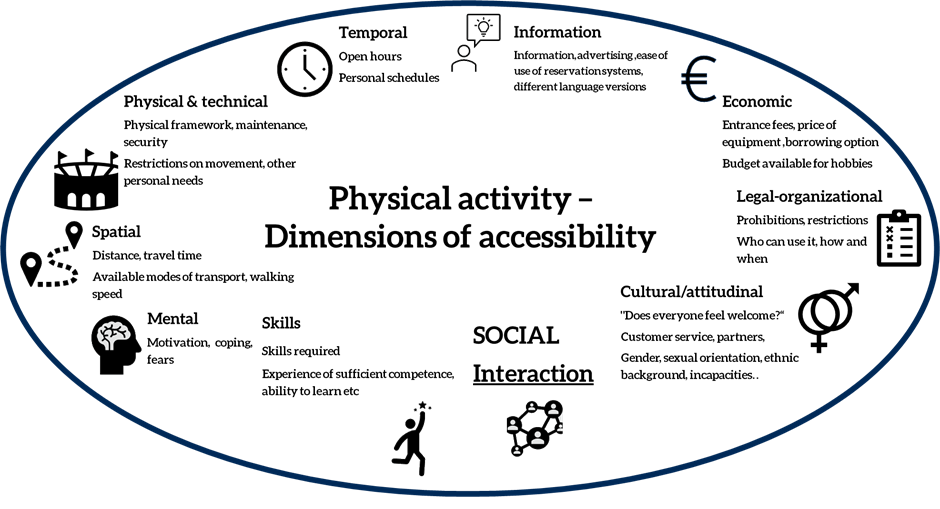

The original idea of the dimensions of accessibility of Physical Activity (PA) was presented in an earlier blog-post (in Finnish). This version has been created as a result of the co-development process with the authorities of our target cities and other parties working in the target suburbs during 2021-2022.

Author: Ilkka Virmasalo (University of Jyväskylä)

The primary purpose for this work is to be a tool for achieving the widest possible understanding of the factors that affect people’s PA. Therefore, it is not purely academic or theoretical in nature but derived from practice. It seeks to outline the phenomenon as universally as possible, but it might be also that it reflects Finnish society better than some other environments. It would be easier to conceptualize the dimensions of accessibility in some predefined environment but here we are trying to deal with the whole range of physical activity: from organized team sport to commuting on foot, or from ski-jumping to a lone walking in nearby nature.

To maximize achievements in promoting PA, the importance of social interaction must also be considered, and interventions need to be targeted to this dimension as well. And that requires a lot of cross-professional and cross-sectorial co-operation to success.

The basic framework was adopted from the Finnish cultural services accessibility website (https://www.kulttuuriakaikille.fi/accessibility). At least in Finland, in cultural services these dimensions have dealt more commonly and profoundly than in physical activity related services. Some dimensions remained unchanged in the revision, some got redefined and two new dimensions were included based on the comments of our co-development partners.

THE DIMENSIONS

Spatial dimension is an easy-to-measure property in principle: the distance of the facility or service from potential users and possibly the time it takes to travel in different ways of travel. This dimension is often involved in planning: especially modern GIS-based services are adopted to support planning. In the target areas of our research – two Finnish suburbs – spatial accessibility does not appear to be problematic – comprehensive possibilities for PA are present in them. Spatial accessibility is a structural problem for sparsely populated areas, especially in the case of built PA-environments.

Physical and technological accessibility form another dimension often present in the planning of PA services and in establishment or renovation projects. Physical/technological dimension of accessibility is the closest to what is usually referred by “accessibility”: ways to build facilities and organize services so that individuals’ physical characteristics affect access as little as possible and that the environment or instruments do not create physical risk for users.

Temporal accessibility in the form of the opening times of the services or facilities, are moderately easy to verify, but it must be remembered that the final interpretation of temporal accessibility is person-dependent: resources in use as well as socially determined interpretations of PA’s desirability affect “whether there is time”.

Informational accessibility – the provision of intelligible information about facilities and services —— is also a clear and important factor affecting people’s PA behavior. In the multicultural target environments of our research, informational accessibility has been more often reported as a factor reducing PA than the lack of venues themselves or their quality. Informational dimension and its’ meaning for potential PA is easy to understand and the interventions to reduce inequality are obvious, but there are always more channels to utilize and need for more languages.

Economic accessibility is an important factor in the perspective of segregation and equality of PA. The costs of physical activity, particularly for those with low income, have been aimed at influencing public administrative measures by allocating financial resources. Although the nature of interventions in terms of economic accessibility is also obvious, some problematics have involved their implementation. It is always tricky demarcation to decide on what basis subventions should be granted: what groups are eligible and what activities are considered so essential that anyone should have an opportunity to practice them? Decision-making needs to align its’ interests in increasing economic accessibility with other economical and political interests.

First “new” dimension, compared to the prior version is cultural/attitudinal dimension. The content of this dimension in this typology is very similar to what is often meant by the “social” dimension. It refers to the characteristics of places and services and its essence crystallizes the question “does everyone feel welcome?” Customer service and other features of the facility/service should appear equal regardless of your ethnic background, gender, bodily composition and so on. There are a lot of potential threats here but awareness of them is improving. in the prior version on dimensions of accessibility these traits were considered to be a part of social dimension, but in this revision the concept of social has been redefined as interaction outside the concrete facilities or services (see below).

Another added facility/service -related dimension is legal-organizational accessibility. It refers to institutionally set restrictions: there might be a perfect spot for skateboarding, but it is not allowed; access to a certain facility may be restricted by membership of a sports club; natural habitats are classified based on conservation values, which in turn determines their potential leisure uses etc. The role of this dimension was clearly highlighted in our interviews with sports authorities, but it is not very widely recognized in planning.

The cognitive and skills-related dimension has been revised into a simpler form for this version. To make the dimension more comprehensible to potential actors who use typology as a tool, it is called more clearly as skills dimension. Skills related accessibility means physical skills and other individual properties that are clearly attached to the environments of physical activity. For example, if You are not capable of swimming, you probably won’t go to swimming pool on your own; in a certain PA facility, there may be technical equipment that requires skills that you do not possess etc.

Another fundamentally individual dimension – already presented in an earlier version – is mental accessibility. It is the layer in which most decisions about attending physical activity are made That is, in mental dimension, an individual’s interpretations of the possibility horizons created by other levels are realized in relation to one’s own needs and motivation.

There are theoretical constructions of accessibility underlining the meaning of motivation and individual decision making, but our vision is that every day social interaction and the historical social construction on “knowing” has much power on explaining activity, too. That is, social dimension does not refer here to some characteristic of a place or a service (in this model, it is cultural/attitudinal dimension), but the space of human activity in which our opinions and thoughts are, at this moment and historically, formed. It is about interaction with other people and dynamics between different groups – in a social-constructionist manner.

THE PROCESS

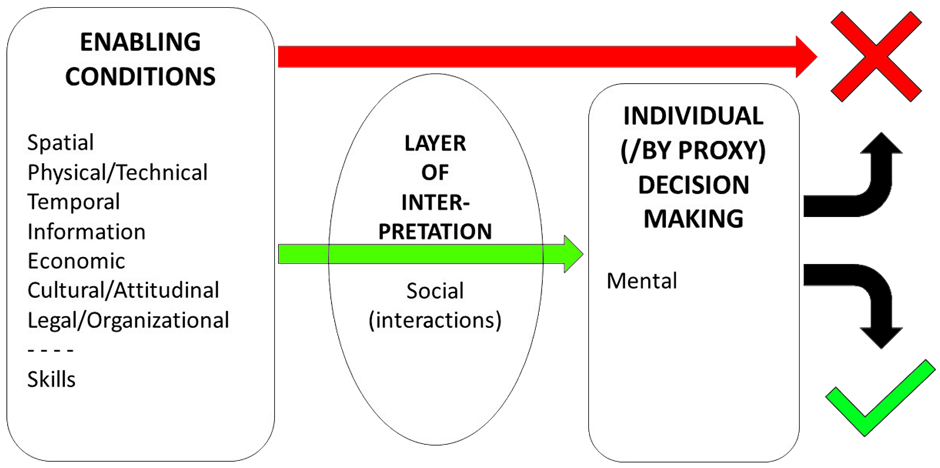

If the realization of PA is thought of as a process, different dimensions have different roles in it. Figure 2 presents a viewpoint, in which accessibility is divided into enabling factors, layer of interpretation and layer of individual decision-making. The leftmost frame contains dimensions that can be seen as “enabling”. Most of them are characteristics of places or services – how they are constructed or organized and what society otherwise does to promote activity. We also count skills dimension as enabling even it is an individual trait.

In this view, the realization of PA is a process in which the social dimension is a lens-like mediator between enabling factors and individual decision-making (mental dimension). This means that who people perceive themselves to be, how they react to situations, and what they perceive their action possibilities to be is based on their previous and current social interactions. Defined in this way, the social dimension is the factor usually appearing as a residual when examining the more easily measurable dimensions – a “black box”. Even if we think that there is no society, or social, outside individuals (individuals are the only actors, no decision is made above them), decision-making is not fundamentally individual process but a consequence on historical continuum. Social dimension is very complex factor including everything that’s happening around You in community and society and in fact it includes Your whole history – and even history before You.

The needs and means of policies designed to promote PA must be articulated in a more democratic and broader perspective and they need to be more inclusive in terms of actors who are thought to be able to stimulate activity.

Social dimension is not strictly deterministic – it does not completely prevent anyone from being active – no red arrow leaving social “lens”. And, not everything is social: the process can be seen as an equation (which it is not – it is a heuristic model) where every condition or dimension should have a value greater than zero. For example: If your financial situation is really bad – You have no money at all – it is impossible to go bowling even if You wanted it how hard. The value of economic dimension is zero and the red arrow on the top leads to “fail” – the possibility for action is not determined socially but materially. Of course, there are numerous other activities that are not depending on Your financial situation, but this desired one is. “By proxy” in the diagram means that someone else is making the decision for You – for example parents deciding for their children.

The traditional Finnish line of promoting physical activity has been an emphasis on the importance of building facilities and organizing services. The promotion of these enabling factors has increased PA, but at the population level, the effects are not entirely desirable. This line, which is focused on developing conditions, best meets the needs of those citizens who are most active and know how to articulate their needs. For the best overall result, it is important to consider how, in addition to creating opportunities, how can we remove barriers of PA, or prevent these barriers from occurring. To maximize achievements in promoting PA, the importance of social interaction must also be considered, and interventions need to be targeted to this dimension as well. And that requires a lot of cross-professional and cross-sectorial co-operation to success. In short: the needs and means of policies designed to promote PA must be articulated in a more democratic and broader perspective and they need to be more inclusive in terms of actors who are thought to be able to stimulate activity.