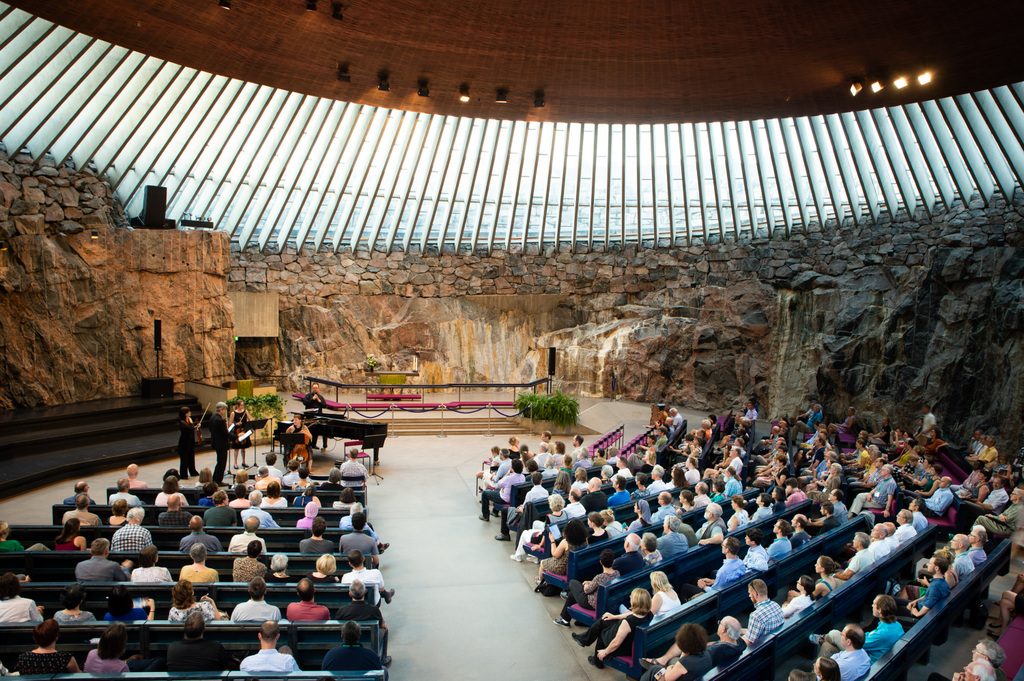

In only two weeks, hundreds of biblical scholars will gather in Helsinki to attend the combined meetings of the European Association of Biblical Studies (EABS) and the International meeting of the Society of Biblical Literature (SBL), which takes place from 31 July to 3 August.

As the meetings are held in our hometown, we hope to showcase to you all the diverse and wide range of research the CSTT is currently engaged in. To make your conference experience easier, we have brought together all contributions by our research centre to this year’s EABS/ISBL meeting.

The contributions are grouped under four headings corresponding to the different research teams in our centre. The list includes contributions from our full and associate members. You can find the abstracts of the papers and more information on the sessions by using the excellent online program book.

We warmly welcome you all to lovely Helsinki!

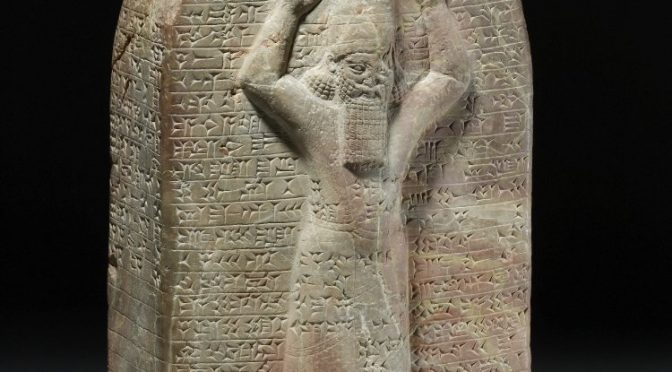

TEAM 1. Society and Religion in the Ancient Near East

July 30 – 16:00–17:30

CSTT-director Martti Nissinen: Presiding in panel discussion “What I Would Like to See Happening in Biblical Studies,” in Opening Session

Aug 1 – 14:00 – 17:00

Martti Nissinen: Presiding, in themed-session “Timo Veijola’s Contribution to Biblical Studies,” in Editorial Techniques in the Hebrew Bible in light of Empirical Evidence (EABS)

Aug 2 – 14:00–17:30

Martti Nissinen: “Why Prophets Are (Not) Shamans,” in themed-session “Shamanism in the Bible and Cognate Literature” in Anthropology and the Bible (EABS)

July 31 – 9:00–11:00

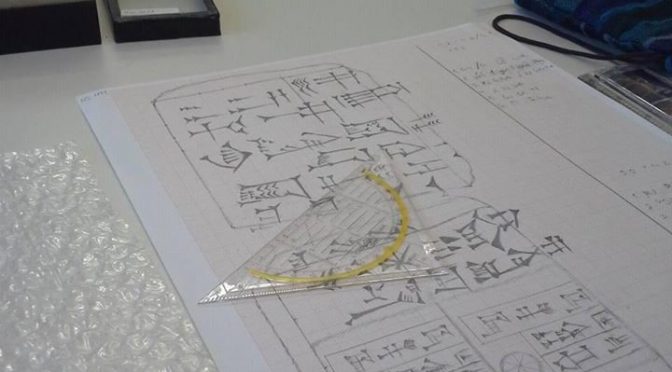

Izaak J. de Hulster: “Hermeneutical Reflections on a Recently Excavated Cylinder Seal Fragment from Abel-beth-maacah,” in Iconography and Biblical Studies (EABS)

July 31 – 14:00–17:00

Izaak J. de Hulster: Presiding, in Iconography and Biblical Studies (EABS)

Aug 2 – 9:00–11:00

Izaak J. de Hulster: “Predecessors of Hilma Granqvist: Women Exploring the Land(s) of the Bible before 1920,” in themed-session “Holy Land Explorers: In Recognition of Hilma Granqvist” inHistory of Biblical Scholarship in the Late Modern Period

Aug 2 – 14:00–17:30

Jason Silverman: “Imperium as Context for Defining “Elite”: Persians and Yahwistic Socio-economic Structure,” in themed-session “Elite Cultures and Achaemenid Koine” inJudaeans in the Persian Empire (EABS)

Aug 2 – 9:00–11:00

Kirsi Valkama: “Aapeli Saarisalo and Biblical Archaeology” in themed-session “Holy Land Explorers: In Recognition of Hilma Granqvist” inHistory of Biblical Scholarship in the Late Modern Period

Aug 2 – 14:00–17:30

Kirsi Valkama and Rick Bonnie: Presiding, in Archaeology and the Biblical World

Aug 1 – 14:00–17:30

Joanna Töyräänvuori: “The Ambiguity and Liminality of the Mediterranean Sea in Ancient Semitic Mythology,” in Ugarit and the Bible: Life and Death (EABS)

Aug 2 – 14:00–17:30

Gina Konstantopoulos: Presiding, in Dispelling Demons: Interpretations of Evil and Exorcism in Ancient Near Eastern, Jewish and Biblical Contexts (EABS)

July 31 – 14:00–17:30

ShanaZaia: “‘My Brothers Were Plotting Evil’: Family Violence in the Ancient Near East,” in Families and Children in the Ancient World

July 31 – 14:00–17:30

Sebastian Fink: “Visual Poetry in Sumerian Lamentations: A Diachronic View,” inDiachronic Poetology of the Hebrew Bible and Related Ancient Near Eastern and Ancient Jewish Literature (EABS)

Aug 1 – 14:00–17:30

Sebastian Fink: “Entering and Leaving This World: Birth and Death in Mesopotamia,” inUgarit and the Bible: Life and Death (EABS)

Aug 3 – 9:00–10:30

Andres Nõmmik: “A Consideration of the City-States of the Late Bronze Age Southern Levant,” in Ancient Near East

Aug 1 – 14:00–17:30

Patrik Jansson: “Prophesying and Twisting: Exploring the Metaphorical Description of Prophesying Women in the Greek Text of Ezekiel 13:17–23,”in Metaphor in the Bible (EABS)

Aug 1 – 14:00–17:30

Lauri Laine: “What God Should Not Be, but Still Somehow Is? Cognitive Perspectives on ‘Theological Incorrectness’,” inWhat a God is Not – the Early History of Negative Theology (EABS)

Aug 2 – 14:00–15:30

Helen Dixon(Wofford College): “Sign, Performance, Possession, Home: What Are Non-royal Phoenician Mortuary Stelae Doing?” in themed-session “Texts in Space” in Ancient Near East

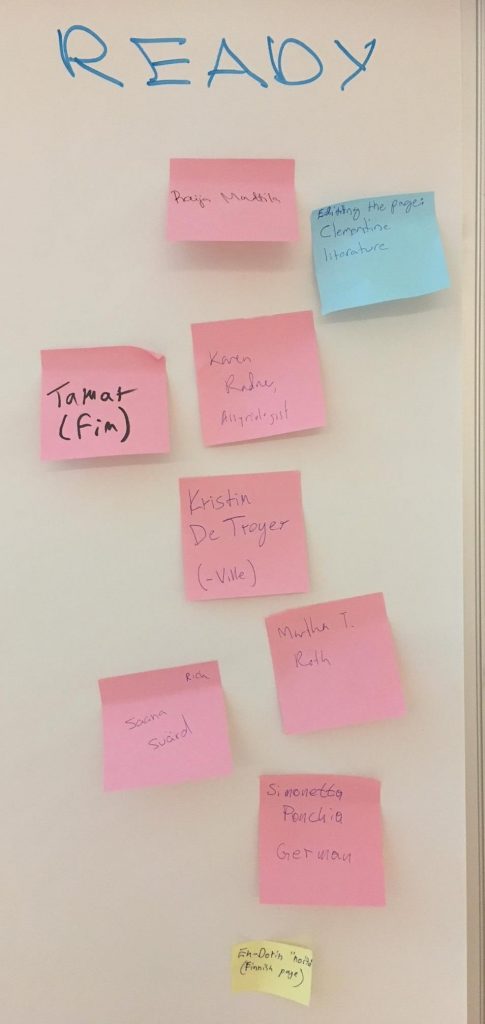

TEAM 2. Text and Authority

Aug 2 – 14:00–17:30

Team 2 leader Anneli Aejmelaeus: “Re-linking 1 Sam 3 and 4,” inSeptuagint of Historical Books (EABS)

Aug 1 – 9:00–11:00

Tuukka Kauhanen: Presiding, in themed-session “Septuagint Syntax” in Septuagint Studies

Aug 2 – 14:00–17:30

Tuukka Kauhanen: “Editing the Septuagint of 2 Samuel,”in Septuagint of Historical Books (EABS)

July 31 – 16:00–17:30

Katja Kujanpää: “Job or Isaiah? What Does Paul Quote in Rom 11:35?” in themed-session “Textual History”, in Septuagint Studies

Aug 2 – 16:00–17:30

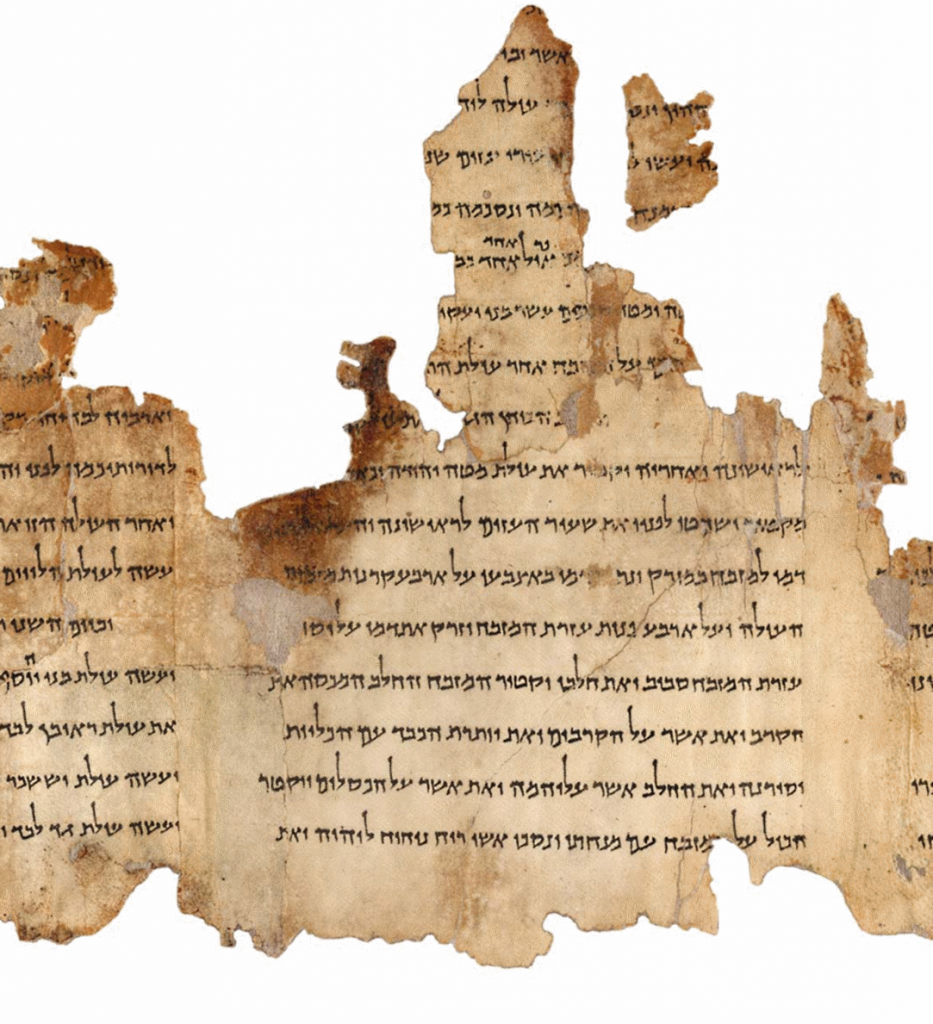

Jessi Orpana: Presiding, in themed-session “History, Kingship and the Economy” in Qumran and the Dead Sea Scrolls

Aug 2 – 14:00–17:30

Paavo Huotari: “Characteristics of the Lucianic Reviser in 2 Samuel,” in Septuagint of Historical Books (EABS)

July 31 – 16:00–17:30

Miika Tucker:“Continuity and Change: A Historical Perspective on the Assessment of Septuagint Jeremiah as a Textual Witness,”in themed-session “Textual History” in Septuagint Studies

TEAM 3. Literary Criticism in the Light of Documented Evidence

Aug 1 – 9:00–11:00

Team 3 leader Juha Pakkala: Presiding, in themed-session “Evoking Coherence in Redactional Processes of Fortschreibung and in Re-writing Biblical Texts” in Developing Exegetical Methods (EABS)

Aug 1 – 9:00–11:00

Mika Pajunen: “The Functions of Extensive Psalms and Prayers in Narrative Contexts,”in themed-session “Evoking Coherence in Redactional Processes of Fortschreibung and in Re-writing Biblical Texts” inDeveloping Exegetical Methods (EABS)

Aug 2 – 9:00–11:00

Ville Mäkipelto: Presiding, in themed-session “Translation Technique and Revisions” in Septuagint of Historical Books (EABS)

Aug 2 – 9:00–11:00

Ville Mäkipelto: Presiding, in themed-session “Joshua 8 – Literary Development in Light of Text, Literary, and Redaction Critical Perspectives” in Editorial Techniques in the Hebrew Bible in light of Empirical Evidence (EABS)

Aug 2 – 9:00 – 11:30

Timo Tekoniemi: Presiding, in themed-session “Editorial Techniques in the Hebrew Bible” in Editorial Techniques in the Hebrew Bible in Light of Empirical Evidence (EABS)

Aug 2 – 14:00 – 17:30

Timo Tekoniemi: Presiding, in themed-session “Textual Criticism” in Septuagint of Historical Books (EABS)

Aug 1 – 14:00–17:00

Reinhard Müller(Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster): “Timo Veijola’s Commentary on Deuteronomy,” in themed-session: “Timo Veijola’s Contribution to Biblical Studies” in Editorial Techniques in the Hebrew Bible in light of Empirical Evidence (EABS)

Aug 2 – 14:00–17:00

Reinhard Müller (Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster):“Eckart Otto’s Models of ‘Urdeuteronomium’ and Deuteronomistic Deuteronomy,” in themed-session: “Eckart Otto’s Commentary on Deuteronomy” in Biblical and Ancient Near Eastern Law

July 31 – 14:00–17:30

Urmas Nõmmik: “Changes in Form and Genre: Five Research Questions,” inDiachronic Poetology of the Hebrew Bible and Related Ancient Near Eastern and Ancient Jewish Literature (EABS)

Aug 1 – 9:00–11:00

Anssi Voitila(University of Eastern Finland): “Usage-Based Translation Syntax of the Septuagint,”in themed-session “Septuagint Syntax” in Septuagint Studies

Aug 3 – 9:00–10:30

Anssi Voitila (University of Eastern Finland): Presiding, in themed-session “Interpretation” in Septuagint Studies

TEAM 4. Society and Religion in Late Second Temple Judaism

July 30 – 16:00–17:30

Team 4 leader Jutta Jokiranta: Member in panel discussion “What I Would Like to See Happening in Biblical Studies,” in Opening Session

July 31 – 14:00–17:30

Matthew Goff (Florida State University) and Jutta Jokiranta:“Survey Results on Ethics and Policies Regarding Unprovenanced Materials” in themed-session “Ethics and Policies Regarding Unprovenanced Materials” inQumran and the Dead Sea Scrolls

Aug 1 – 9:00–11:00

Jutta Jokiranta: Presiding, in themed-session “Ritual and Qumran” in Ritual in the Biblical World

Aug 2 – 14:00–17:30

Raimo Hakola:“The Ancient Synagogue at Horvat Kur, Galilee: Excavations 2010-2018,” in Archaeology and the Biblical World

July 30 – 16:00–17:30

Rick Bonnie: Member in panel discussion “What I Would Like to See Happening in Biblical Studies,” in Opening Session

July 31 – 14:00–17:30

Rick Bonnie: ”Researching Cultural Objects and Manuscripts in a Small Country: The Finnish Experience of Raising Awareness of Provenance, Legality, and Responsible Stewardship,” in themed-session “Ethics and Policies Regarding Unprovenanced Materials” in Qumran and the Dead Sea Scrolls

Aug 1 – 9:00–10:30

Elisa Uusimäki: Presiding, in themed-session “Gendered Virtue?” in Virtue In Biblical Literature (EABS)

Aug 1 – 16:00–17:30

Charlotte Hempel (University of Birmingham) and Elisa Uusimäki: Presiding, Early Career Development Workshop

Aug 2 – 9:00–11:00

Elisa Uusimäki: “Is There ‘Virtue’ in Semitic texts? An Analysis of the Testament of Qahat,” in themed-session “Is there Virtue in Semitic texts?” in Virtue In Biblical Literature (EABS)

Aug 2 – 14:00–17:30

Elisa Uusimäki: Presiding, in themed-session “Portraying Virtue” inVirtue In Biblical Literature (EABS)

Aug 3 – 9:00–11:00

Elisa Uusimäki: Presiding, in themed-session “Open Session” in Qumran and the Dead Sea Scrolls

Aug 1 – 14:00–17:30

Katri Antin:“Intellectual Illumination as a Visionary Experience,” in themed-session “Visions and aspects of Spatial Theory – Focus OT” in Vision and Envisionment in the Bible and its World (EABS)

Aug 3 – 9:00–11:00

Katri Antin:“Implicit Exegesis as a Mean of Transmitting Divine Knowledge in the Thanksgiving Psalms,”in themed-session “Open Session” in Qumran and the Dead Sea Scrolls

Aug 1 – 16:00–17:30

Hanna Tervanotko: Member in panel discussion “Teaching Gender and the Bible,” in Status of Women in the Profession

Aug 2 – 14:00–17:30

Hanna Tervanotko: “Reading 1 Samuel 28 and Odyssey 11 through the Lens of Shamanism,” in themed-session “Shamanism in the Bible and Cognate Literature” inAnthropology and the Bible (EABS)

Aug 1 – 14:00–15:30

Sami Yli-Karjanmaa: “Philo’s Reincarnational Anthropology: A Comparison with Clement,” in themed-session “Philo of Alexandria” in Judaica

Aug 3 – 9:00–11:15

Hanna Vanonen: “Apocalyptic Vision or Ritual Instructions? The Qumran War Texts as Apocalyptic Literature,” in themed-session “Apocalyptic Literature: Second Temple Judaism” in Apocalyptic Literature