Text by Paola Minoia

This is a note from the presentation at the Develop! kick-off seminar organized by the Academy of Finland in Paasitorni Congress Centre, Helsinki 26.11.2018

Our project addresses the problematic relation between formal education and indigenous rights. Education is a fundamental field for cognitive recognition and rights, and this is why indigenous organizations have positioned the goal of intercultural education high in their agenda. Ecuador is a plurinational state, as stated by the 2008 Constitution, which means that all nationalities and ethnic groups have the right to equal representation in the country. Therefore, the main goal of our Academy-funded project is to support the recognition of Amazonian indigenous ecological and cultural knowledges as part of quality education.

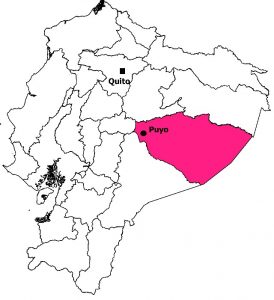

Our focus is especially the Pastaza province, an area of wide biological and cultural diversity, in the Amazonian region. The region is inhabited by 7 out of the 14 native groups living in Ecuador, namely: Achuar, Andoa, Shuar, Kichwa, Sàpara, Shiwiar, and Waorani. They are recognized as nationalities by the State; however, their very cultural identity is endangered. All are at risk of cultural assimilation, migration and territorial loss, for land grab, oil extraction and commercial plantations.

Education is one of the greatest drivers of empowerment, and a right to all, as the Sustainable Development Goal number 4 states. However, let´s unpack this principle of “quality education as a right for all”, in an ethnically diverse state like Ecuador: there is not a fit-for-all education model, nor quality can be evaluated according to one overarching academic canon. Education for all has to be grounded on recognition of diverse epistemologies, and on the right for all different indigenous nationalities to have their ancestral knowledges and worldviews integrated in their school programmes. Secondly, the right to education has to be combined with the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous peoples, adopted in 2007, affirming the indigenous peoples’ rights to establish and control their educational systems and institutions. On this ground, education has to be guaranteed through the indigenous peoples’ right to run their community schools and programmes in their languages through their diverse pedagogies. In Ecuador, since the late 80ies, and especially after the uprising of the indigenous peoples in 1990 and 1992, deep interculturality has been interpreted as a means for emancipation, self-determination and territorial integrity of the indigenous nationalities by the indigenous organizations, and by the umbrella organization CONAIE.

Unfortunately, during the past decade, despite the Constitution, a change of politics decided by the Correa government marked a violent stop to the liberation process. The economic crisis linked to the fall of oil prices was addressed by an increased push for oil exploitation. The intercultural bilingual project was closed; not because of a stop in government spending in education, on the contrary; but because it was substituted by a project of modernization through mainstreaming schooling in Spanish (especially through the Millennium schools project), hindering de facto the reproduction of indigenous ecological subjectivities and socio-cultural practices. Many rural schools were closed and new large school compounds were built, hiring international faculties. Reaching the schools is difficult for families living in the remote areas; many of them have moved to town, while others try to resist, to avoid detaching from their lands and their communities.

Since July 2018, the new president Lenin Moreno relaunched a cooperative relation with CONAIE for the reintroduction of the intercultural bilingual education, with an ambitious programme of reforms; the agreement has included the reopening of the indigenous university Amawtay Wasi, that had been closed in 2013 and will restart offering course programmes in 2020.

In this framework, our project aims to observe the situation in upper secondary schools of Pastaza, in Universidad Estatal Amazónica (UEA), other universities and the Amawtay Wasi, to see the realities of education in the territories of the Amazonian region: what facilitates or hinders access to schooling; and how quality education is enhanced in the new intercultural project between CONAIE and the State. We expand the concept of culture to involve ecological knowledge since human-nature beings are deeply intertwined.

The project is divided into 4 components:

- Spatio-temporal dimension of accessibility to education

- Intercultural education programmes and culturally responsive education

- Indigenous students transitions from upper secondary to tertiary education and work

- Politics of intercultural education and observatory on education

The spatio-temporal dimension addresses the situation of mobility, also discussing the consequences of the closing of community schools after 2011; the accessibility of the new millennium school establishments; and observing forthcoming re-openings promised by the central state: 1000 schools should reopen already in 2019. We make a quali-quantitative analysis and mapping of the distances, walks and means of transport, danger and discomforts and possible solutions.

The second component aims to study course contents, teachers’ background, and the new construction of the intercultural programmes in upper secondary schools, at the UEA and in the Amawtay Wasi university. The questions are, to what extent are the taught subjects intercultural? How do they reflect holistic epistemologies and the pluriverse? What is the content for instance, of integrated sciences, humanities and cosmovision (subjects included in the intercultural curricula), and through what pedagogies are they taught? We have seen that cultures are represented in terms of languages, festivities, songs, and other heritage; but how are all forms of life, places, earth beings and local socio-ecological systems represented? Indigenous pedagogies put emphasis on fieldwork and contextuality, revealing places through their history, their names, their meanings.

In the plans of the intercultural education institutions, school programmes have been linked, at least theoretically, to the environmental and livelihoods cycle of the indigenous territories. For this, each school is now preparing the “calendarios vivenciales educativos”: but as for now, they are only based on the Andean cycles. Are the Amazonian beings represented? Is nature there represented only in terms of agro-ecological cycles, and thus, only as a reflection of the functional relations that humans assign to nature?

The third component will address the question of the challenges for students and families of choosing intercultural bilingual education schools instead of mainstream schooling in Spanish. There is a fear among parents that it could undermine the future of their children. That is why quality is important, as well as the public recognition of interculturality as a relevant model of education for any future career. We will start by considering documents prepared by youth representatives of CONAIE to understand and potentially address the challenges of transitions of students from intercultural schooling to state universities, to work life in all possible sectors, and to become empowered citizens.

Finally, our aim is to support the voice of minorities in the Amazonian region that are hidden by the government-indigenous relation that, so far, has only involved mestizos and kichwa from the Andes. We will offer our data, analysis and public reporting of discussions in this theme through collaboration between the education sector and the indigenous representative organizations. We will advocate the relation between knowledge diversity and formal education, and the maintenance of forest biodiversity, and territorial conservation in the Amazonian region. We will do it through a repository of data, workshops and public presentations.

Our work will be side-by-side with the indigenous nations and their cultural regeneration project, by asserting complexity and truthfulness of located knowledges, instrumental for autonomy and self-determination in their territories. Our group is formed by researchers from the University of Helsinki, from the Universidad Estatal Amazónica, and representatives of CONFENIAE and CONAIE.