Text: Tuija Veintie

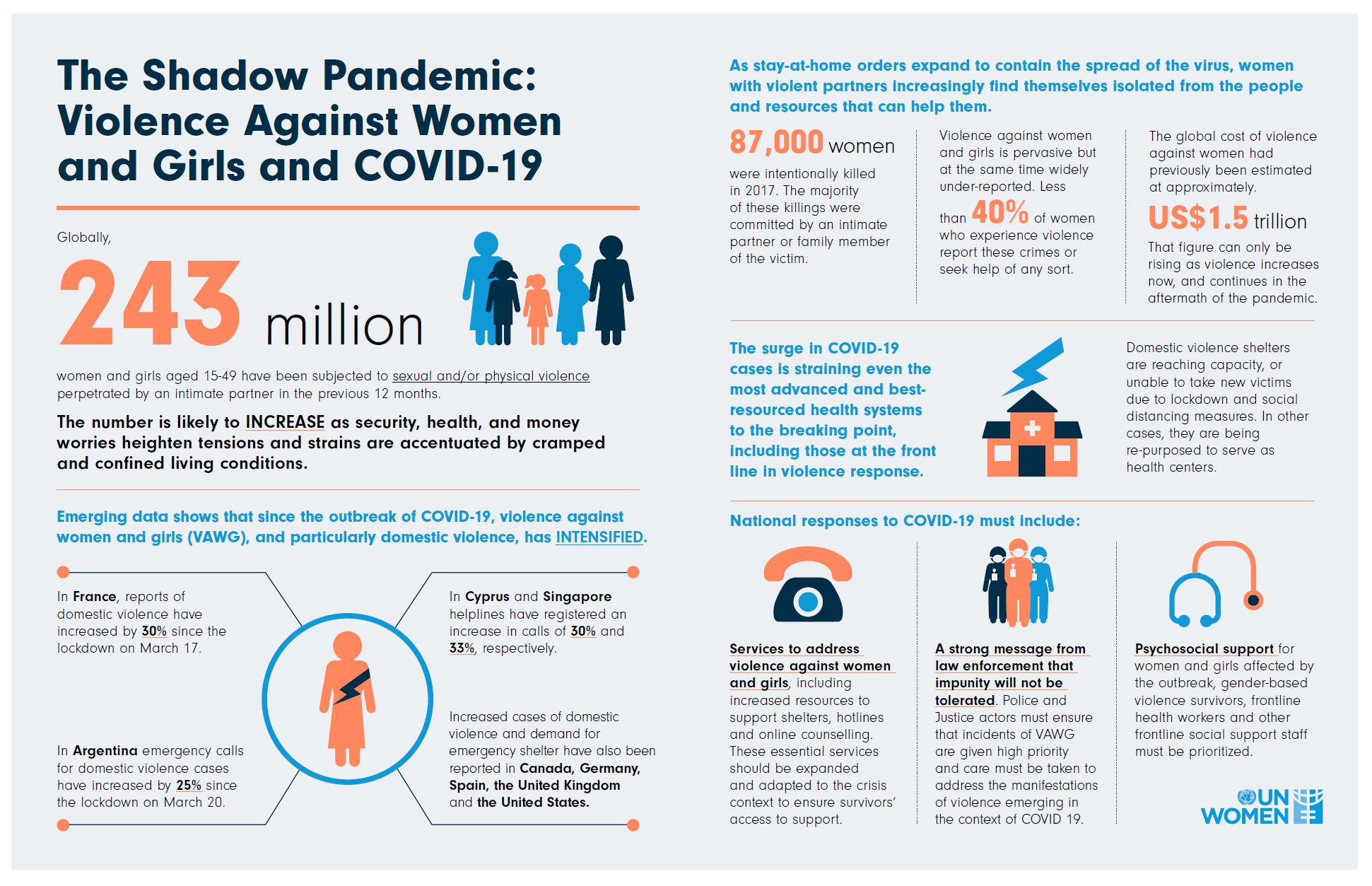

International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women on 25th of November reminds about the worldwide problem of gender-based violence. Women and girls are particularly at risk of experiencing violence in times of social and economic crisis. This year, the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic has threatened the health and well-being of people around the world, deepening social and economic inequalities, exacerbating poverty. At the same time, violence against women and girls, and particularly domestic violence, has intensified globally, according to the United Nations (UN, 2020).

Also in Ecuador, domestic violence against women and girls has been increasing during the pandemic. Among others, Indigenous women living in the outskirts of big cities and in rural communities run a particular risk of experiencing violence due to their vulnerable socio-economic situation (Sacha Samay, 2020). Moreover, recent reports bring forward many other forms of violence that Indigenous women experience at the same time when they carry a heavy load of unpaid and unacknowledged care work in their families. In a declaration released in commemoration of the International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women, the women representing the Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of Ecuador (CONAIE) highlight the multiple forms of violence that Indigenous and rural women experience:

“as physical and sexual violence that many times ends up in femicide; as economic violence when our work is not valued and we do not have the necessary conditions to make the land produce and to commercialize our products; we live the obstetric violence when the medical system abuses us without understanding on our cosmovision; we live symbolic violence when we are discriminated for being Indigenous, and for living in rural areas; the violence is also present in our territories when invaded by the military forces and when destroyed or contaminated with mining, petroleum, and monoculture farming; we live political violence when we are prevented from holding public positions.” (CONAIE, 2020a. Translation from Spanish by author).

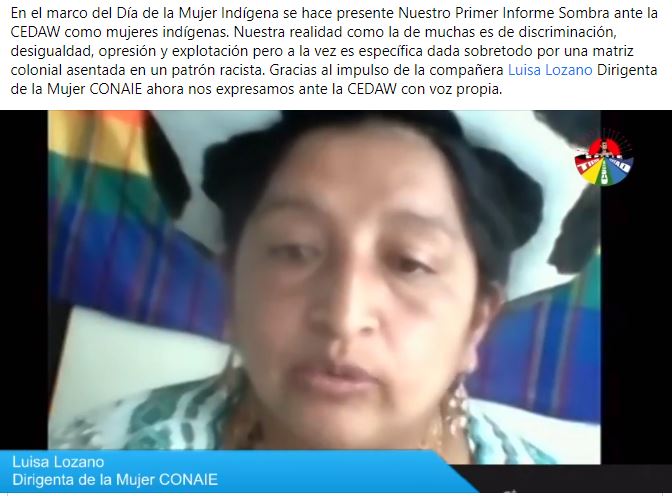

Structural violence that marginalizes Indigenous women from public policy decision making, violates their individual and collective rights as women and as Indigenous people e.g. in relation to the territorial rights, and widens the social inequalities, is discussed also in a recently published shadow report to the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW). This shadow report, produced by Indigenous women representing various Indigenous organizations, focuses on discrimination against Indigenous women particularly with relation to territorial rights, education, employment, reproductive rights and obstetric violence, and discrimination against rural women.

With regard to education, the shadow report highlights the unequal access to education, particularly at the time of confinement and virtual education. In many cases, virtual education is not viable as Indigenous students and teachers living in rural areas rarely have access to internet and communication technologies, as indicated in our earlier blog post (Hohenthal, Machoa & Veintie, 2020). The shadow report to CEDAW remarks that the Ecuadorian government does not provide data on the dropout rates by sex and ethnic group, which makes it difficult to assess the consequences of the current educational situation for Indigenous girls and women in particular.

“At this critical moment, with COVID-19 exacerbating gender inequalities, we must renew our commitment to educating girls and women. Progress in this field echoes through generations – as do reversals of this progress.” says the UNESCO Director-General Audrey Azoulay in the foreword of the latest Global Education Monitoring (GEM) Gender report, released in October 2020. The GEM Gender report notes that since the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (1979) and the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action (1995) that landmark the international community’s commitment to advancing women’s rights, there has been considerable improvement in terms of equal access to education worldwide. However, girls are still more likely to experience educational exclusion compared to boys.

As exemplified in the GEM Gender report, exclusion and marginalization occurs in different forms in education, and requires action in the level of educational policies, teacher education, educational materials, curriculum and instruction. One of the critical areas to tackle is to support pregnant girls and young parents to go to school. Early pregnancy rates remain high in many parts of the Global South, and in some countries, pregnant girls may be banned from school (UNESCO, 2020). Even if not banned, pregnancy still tends to increase the likelihood of dropping out of school. In our field studies in the Ecuadorian Amazonia before the COVID-19 pandemic, we observed that pregnancy and starting a family were the most commonly mentioned reasons for Amazonian Indigenous girls to dropout before completing their upper secondary education.

The Ecuadorian Indigenous Women’s report to CEDAW, GEM Gender report, and reports concerning gender-based violence and femicides around the world, indicate we are still far from having eliminated violence and discrimination against women, and plenty of work to do towards equality. In words of Jaime Vargas, president of CONAIE and Luisa Lozano, leader of the women in CONAIE:

“The struggles carried out by indigenous women do not only contemplate stopping the multiple forms of violence, they have a broader meaning: to defend the right to life, to make decisions about their bodies, to territories and natural resources, for all the women who are now unjustly prosecuted, for all the mothers and wives who are victims of domestic violence, for all the women who are victims of exclusion and invisibility in work, organizational, and educational spaces, together we will continue in the struggle to advance towards a development based on equality for all. Long live the women’s struggle!” (CONAIE 2020b. Translation by author),

Referred reports:

Informe sombra Mujeres indígenas al Comité de la CEDAW. 2020. https://drive.google.com/file/d/14kGgrgvhBTn3fb27cjd-LDV7Bxb68i6_/view

UNESCO 2020. Global Education Monitoring Report. Gender Report. A new generation: 25 years of efforts for gender equality in education. https://en.unesco.org/gem-report/2020genderreport

Other referred sources:

CONAIE, 2020a. Manifiesto mujeres indígenas y campesinas del Ecuador. Día internacional de la no violencia contra la mujer. ¡No más violencias! Via Comunicación CONFENIAE. [25.11.2020] https://www.facebook.com/comunicacionconfeniae.redacangau/photos/pcb.2899302200301183/2899302153634521

CONAIE, 2020b. 25n: Día internacional de la eliminación de la violencia contra la mujer. [25.11.2020] https://conaie.org/2020/11/25/25n-dia-internacional-de-la-eliminacion-de-la-violencia-contra-la-mujer/

Hohenthal, Machoa & Veintie, 2020. Exclusive distances: intercultural bilingual education during the COVID-19 pandemic in Ecuadorian Amazonia.

United Nations (UN), 2020. International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women, 25 November. https://www.un.org/en/observances/ending-violence-against-women-day

Sacha Samay, Soplo de vida en tiempos de pandemia. Capítulo seis: La justicia de las mujeres. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AVKbScKgUqw&feature=youtu.be&fbclid=IwAR0Xiy3yj_3dpO81i6GkEQ9iEE9MpumzWyItcuNBAmWdkmHX-KlgoPlNynM