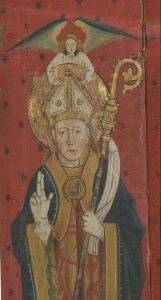

Joulupukkinakin tunnetun Pyhän Nikolaus Myralaisen pyhimysattribuutteihin eli tunnusmerkkeihin kuuluu kirja, jonka päällä hän kannattelee kolmea kultaista palloa – lahjoja, jotka pelastivat köyhän isän kolme tytärtä kurjuudelta – sekä klassiset piispan varusteet hiippoineen, hansikkaineen ja sauvoineen. Näin hänet on kuvattu ruotsalaisen Kråksmålan kirkon alttarikaapin ovipaneelimaalauksessa. Mutta mikä valkoinen liina on kiinnitettynä sauvan yläosaan?

Pyhä Nikolaus Myralainen Kråksmålan kirkon alttarikaapin ovipaneelissa, yksityiskohta. Maalaus on ajoitettu vuosiin 1450-1475. Kuva: Lennart Karlsson / SHM (CC-BY-NC-ND).

Kyseessä on keskiajan kirkollisiin perinteisiin kuuluva esine nimeltään pannisellus, jonka osaksi Suomessa on tullut katoaminen ja unohtuminen. Yhtäkään keskiaikaista pannisellusta ei tiettävästi ole säilynyt suomalaisissa kirkoissa tai museoissa edes fragmenttina. Sen nimikin lienee useimmille lukijoille tuntematon.

Nimi pannisellus perustuus latinan sanaan pannus, joka tarkoittaa liinaa tai kangasta. Toinen samasta esineestä käytetty termi on sudarium, joka on tunnetumpi pyhän ja kiistellyn reliikin, Kristuksen hikiliinan nimityksenä. Pannisellus-sudarium kuului keskiajalla piispansauvan oheistarvikkeisiin. Se oli yleensä kiinnitettynä nauhalenkillä piispansauvan yläosaan, mutta se voi olla myös piispan kädessä, lenkki sormen ympärillä. Hikeen viittaava termi sudarium lienee syynä siihen, että liinan funktioksi on usein selitetty piispansauvan suojaaminen piispan käden hikoilulta (ks. esim. Kyrkans föremål, 152). Kuten Pyhän Nikolauksen kuvastakin näkyy, piispan virka-asuun tosin kuuluivat myös hansikkaat, joita käytettäessä suojaus ei olisi ollut tarpeen. Liinalla on silti voinut alkujaan olla käytännöllinen tarkoitus, mutta ainakin myöhäiskeskiajalla se oli ensisijaisesti koriste ja piispan arvon symboli (Schaefer & Hummel 1947, 81–82; Von Euw 1985, 401, 453).

Itse havahduin piispallisen sudariumin olemassaoloon tarkastellessani Turun piispan, autuaan Hemmingin kuvaa Urjalan alttarikaapin oven sisäpaneelissa. Vuoden 1500 paikkeilla maalattu kuva on ainoa jokseenkin varma keskiaikainen kuvaesitys 1300-luvulla eläneestä Hemmingistä, ellei mukaan lasketa hänen piispansinettiään, jossa häntä edustaa melko geneerinen piispahahmo hiippoineen ja sauvoineen (ilman liinaa).

Autuas Hemming -maalaus Urjalan alttarikaapin oikeanpuoleisessa ovipaneelissa, yksityiskohta. Alttarikaappi on valmistettu vuoden 1500 paikkeilla todennäköisesti Ruotsissa. Tampereen museokeskus, HM 156:1. Kuva: Jari Kuusenaho, Vapriikin kuva-arkisto.

Urjalan alttarikaapin maalauksessa piispa pitelee koristeellista paimensauvaansa, jonka yläosasta riippuu pannisellus. Saman alttarikaapin toisessa ovessa on kuvattuna Pyhä Henrik, jolla on myös piispansauva ja pannisellus, mutta liinaa ei ole kuvattu yhtä näkyvästi kuin Hemmingillä. Kummallakin piispalla liina on osittain käden ja sauvan välissä.

Urjalan maalaus herättää kysymyksen, miksi en ole aiemmin kiinnittänyt huomiota liinan olemassaoloon, jos se oli tavallinen osa keskiaikaisen piispan varustusta. Kuuluuko pannisellus keskiaikaisten piispakuvien ikonografiaan yleisemmin? Onko se keskiajan tutkijalle niin tuttu näky, että en ole huomannut ihmetellä sitä? Yksi syy huomaamattomuuteen lienee myös se, että keskiajan taidetta käsittelevissä teksteissä liinaa ei yleensä erikseen mainita piispojen kuvien yhteydessä, vaikka sauva mainittaisiinkin. Esimerkiksi piispa Hemmingin ikonografiaa käsitelleet Birgit Klockars (1960, 224–226) ja Tryggve Lundén (1955, 71–78) jättävät sekä piispansauvan että liinan huomiotta kirjoittaessaan Urjalan Hemming-maalauksesta.

Pikainen katsaus Suomessa ja Ruotsissa säilyneisiin kuviin osoittaa, että liina ei ole kuvissa esiintyvien piispojen vakiovaruste. Pyhän Henrikin sarkofagin kansilevyn kuvassa Nousiaisissa piispan sauvan tienoilla liehuu kangaskaistale, mutta tarkemmin katsottuna se onkin sauvan takana leijuvan enkelin helma; toinen samanlainen enkeli helmoineen on piispan toisella puolella.

Toistaiseksi ainoa toinen Suomen keskiajan kuvastosta löytämäni pannisellus on Missale Aboensen kansikuvassa: siinä Pyhän Henrikin piispansauvassa on liina, mutta hänen oikealla puolellaan polvistuvan Turun piispa Konrad Bitzin sauvassa (jota pappi pitelee Bitzin puolesta) sitä ei ole.

Pyhä Henrik, piispansauva ja sudarium Missale Aboensen kansikuvassa, 1488. Kuva: Wikimedia Commons / Jyväskylän yliopisto (https://missale.jyu.fi/).

Högsbyn kirkon alttarikaapin paneelimaalauksissa kuvatuilla piispa Henrikillä ja pyhällä Sigfridillä sekä tuntemattomalla piispalla on kullakin sauvassa pannisellus, mutta samassa teoksessa esiintyvillä kirkkoisillä puolestaan ei. Tämän katsauksen perusteella ei vielä ole pääteltävissä, mitä liinan mukanaolo tai puuttuminen tarkoittaa. 1500-luvulta lähtien pannisellus on kuulunut ensisijaisesti apotin tai abbedissan sauvaan (Jacobs 2018), mutta pohjoismaisessa kuvastossa se näyttää liittyvän nimenomaan piispoihin.

Pyhä Sigfrid Högsbyn kirkon alttarikaapissa, yksityiskohta. Alttarikaappi on pohjoissaksalaista työtä 1400–1500-lukujen vaihteesta. Kuva: Lennart Karlsson / SHM (CC-BY-NC-ND).

Termejä pannisellus tai sudarium ei mainita suomalaisessa tai ruotsalaisessa keskiajalta säilyneessä asiakirja-aineistossa. Tästä voisi herätä ajatus, että ilmiö ei olisi lainkaan levinnyt Pohjolaan ja että liinojen esiintyminen edellä mainituissa maalauksissa ja missalen kuvassa johtuisi ulkomaisesta vaikutuksesta kuten mallikuvista. Liinan näkymättömyydelle asiakirjalähteissä voi olla muita syitä. Pienehkö kangasesine ei todennäköisesti ollut riittävän merkittävä tai arvokas tullakseen erikseen kirjatuksi esimerkiksi osana piispan omaisuusluetteloa tai testamenttia saati mainituksi kirjeessä tai kronikassa muiden piispan tarvikkeiden ohella.

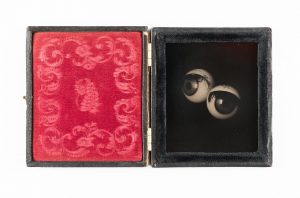

Kaikeksi onneksi Ruotsissa on säilynyt ainakin neljä todistuskappaletta siitä, että esine voi olla olemassa, vaikka siitä ei olisi kirjallisia alkuperäislähteitä. Ruotsin historiallisen museon kokoelmissa on kaksi pannisellus-liinaa, jotka on ajoitettu myöhäiskeskiajalle, jotakuinkin 1500-luvun alkuun. Toisesta liinasta on itse asiassa jäljellä vain kolmiomainen yläosa ja siihen kiinnitetty nauhalenkki, jolla se on ripustettu piispansauvan yläosaan.

Skepptunan pannisellus-fragmentti, 1500-luvun alku. Historiska museet, Tukholma. Kuva: Ola Myrin, SHM (CC BY 4.0).

Löydettäessä kyseinen liinafragmentti oli ripustettuna Skepptunan kirkossa olleen Thomas Becket -pyhimysveistoksen piispansauvaan. Siitä ei ole tietoa, onko liinaa mahdollisesti käytetty nimenomaan veistoksen yhteydessä jo keskiajalla vai onko se aiemmin kuulunut elävälle piispalle.

Skepptunan kirkon Thomas Becketiä esittävä veistos katetulla valtaistuimellaan. Piispansauvassa riippuu kopio siihen aiemmin kuuluneesta pannisellus-liinan fragmentista. 1400-luvun loppupuoli. Historiska museet, Tukholma. Kuva: Mattias Malmberg, SHM (CC BY 4.0).

Toinen, kokonaisena säilynyt ja monipuolisesti kirjailuin, nauhoin, helmin, paljetein ja tupsuin koristeltu pannisellus on Vadstenan birgittalaisluostarin tuotantoa 1500-luvun alkupuolelta. Sen löytöpaikka on tuntematon. Paitsi yläosassa, myös alempana liinassa näkyy kirjailua samoin kuin Kråksmålan alttarikaapin Pyhän Nikolauksen liinassa. Skepptunan esimerkin valossa voisimme myös spekuloida, onko tämä liina kuulunut piispan vai piispaveistoksen varusteisiin tai ehtinyt kenties olla kummassakin käyttötarkoituksessa.

Vadstenassa valmistetun pannisellus-liinan yläosa, 1500-luvun alku. Historiska museet, Tukholma. Kuva: SHM (CC BY 4.0).

Uppsalan tuomiokirkon kokoelmiin kuuluu myös yksi kokonainen pannisellus ja yksi sellaisen yläosa, jotka oli aiemmissa esineluetteloissa virheellisesti merkitty Pyhän Birgitan saksikoteloksi, neulatyynyksi ja esiliinaksi, kunnes tekstiilihistorioitsija Agnes Branting tunnisti niiden oikean esinetyypin (Branting 1910, 175–178). Näistäkin kokonainen pannisellus on sen yläosaan, IHESUS- ja MARIA-monogrammien oheen kirjailtujen ristien muodon perusteella yhdistetty Vadstenaan (Branting & Lindblom 1928, 106). Liinansa menettäneessä pannisellus-yläosassa puolestaan on kirjailtu piispansauva sekä kuvioita, jotka tekstiilitutkija Inger Estham on tulkinnut viittaukseksi birgittalaissääntökuntaan (Ordo Sanctissimi Salvatoris). Esthamin mukaan on pääteltävissä, että molemmat Uppsalan pannisellus-liinat on valmistettu Vadstenan luostarissa arkkipiispa Jöns Håkanssonin käyttöön, ensimmäinen mahdollisesti hänen arkkipiispavihkimykseensä ja toinen käytettäväksi Vadstenan luostarikirkon vihkimisjuhlassa (Estham 2010, 261–264).

Pannisellus-fragmentti Uppsalan tuomiokirkosta, 1400-luvun loppu? Kuvaaja tuntematon, Riksantikvarieämbetet. Public domain.

Turun tuomiokirkkomuseon kokoelmiin kuuluu piispansauva, jonka koukkupää on kadonnut. Arkeologit Heini Kirjavainen ja Visa Immonen ovat saaneet selville, että sauvassa on keskiaikaisia osia, mutta sitä on nähtävästi korjailtu uusilla osilla vielä 1600-luvulla tai myöhemmin (Kirjavainen & Immonen 2016, 97–102). Sauvaan on keskiajalla todennäköisesti kuulunut myös pannisellus. Kun piispansauvan käyttö virallisesti lopetettiin Ruotsin valtakunnassa ja siten myös Suomessa 1500-luvun lopulla, myös pannisellus-liinat katosivat kirkoista. Suomessa luterilaisilla piispoilla piispansauvat otettiin uudelleen käyttöön 1930-luvulla (Immonen 2011, 147), mutta liina ei tehnyt paluuta niiden mukana.

Lähes kaikki pyhiä piispoja esittävät puuveistokset suomalaisissa kokoelmissa ovat menettäneet sauvansa ja usein myös kätensä, mutta jäljellä olevissa sauvoissa ei näy merkkejä liinasta. Kun liina puuttuu useimmilta maalatuilta tai piirretyiltä piispoilta, voimme olettaa, että se ei ole ollut välttämätön osa veistoksissakaan. Skepptunan Thomas Becket -veistoksen ansiosta on kuitenkin helppo kuvitella, että vaikka pannisellusta ei olisi veistetty kuviin mukaan, se on voitu liittää veistoksiin kankaisena. Muitakin sittemmin kadonneita veistosten ”lisäosia” tunnetaan: monille pyhimyskuville tehtiin erikseen metallinen kruunu, ja veistosten harteille saatettiin pukea viitta (ks. esim. Kirjavainen 2015, 324–336; Räsänen 2009, 71–72). Näistä käytännöistä ja esineistä on säilynyt vain vähän jälkiä. Veistosten kruunuista ja viitoista on säilynyt asiakirjamerkintöjä lähinnä siinä tapauksessa, että ne ovat sisältäneet hopeaa. Vaatimattomampi pannisellus on jäänyt merkitsemättä niin alttarien omaisuusluetteloihin kuin piispojen testamentteihinkin.

Kadonneet esineet ovat fragmenttien tavoin menneisyyden kulttuuriperinnön puuttuvia palasia, joiden tutkiminen haastaa perinteisiä taidehistorian menetelmiä. Toisaalta juuri esineiden, kuvien tai lähdeaineistojen poissaolo voi herättää tutkijan mielenkiinnon ja avata uusia näkökulmia, kuten taidehistorioitsijat Beate Fricke ja Aden Kumler toteavat artikkelikokoelman Destroyed – Disappeared – Lost – Never Were esipuheessa (2022).

Sudarium tai pannisellus on varmasti ollut osa keskiajan piispojen – sekä lihallisten että puisten – esinemaailmaa ja laajemmin tekstiilistä kulttuuriperintöä myös Suomessa. Liinojen määrää myöhäiskeskiajan Suomessa ja Ruotsissa on mahdotonta arvioida, mutta vähintään yksi on todennäköisesti kuulunut jokaisen piispan liturgiseen välineistöön. Kirjallisten aikalaislähteiden puuttumisesta huolimatta jo fragmentoituneilla esineillä ja muutamalla kuvalla on kyky havainnollistaa liinan olomuotoa ja käyttöä sekä voima pelastaa ilmiö lopulliselta unohtumiselta. Aiemmin tunnistamattomaksi jäänyt pannisellus voi vielä löytyä suomalaisista kokoelmista, mutta vaikka niin ei kävisi, samasta keskiaikaisesta Uppsalan arkkihiippakunnasta peräisin olevilla ruotsalaisilla esimerkeillä on Suomenkin kannalta oleellinen todistusarvo.

Sofia Lahti

Kirjallisuutta:

Branting, Agnes 1910, Några meddelanden om svenska mässkläder. Fornvännen 1910, 169–185.

Branting, Agnes & Andreas Lindblom 1928–29, Medeltida vävnader och broderier i Sverige. Uppsala: Almqvist & Wiksell.

Estham, Inger 2010, Textilsamlingen från 1200-talet till 1860-talet. Uppsala domkyrka. V. Inredning och inventarier. Av Herman Bengtsson, Inger Estham och R. Axel Unnerbäck med bidrag av Sabine Stein. Uppsala: Upplandsmuseet, 213–341.

von Euw, Anton 1985, Liturgica. Ornamenta ecclesiae: Kunst und Künstler der Romanik. 1. Katalog zur Ausstellung de Schnütgen-Museums in der Josef-Haubrich-Kunsthalle. Herausgegeben von Anton Legner. Köln: Schnütgen_Museum, 385–483.

Fricke, Beate & Aden Kumler 2002 (toim.), Destroyed – Disappeared – Lost – Never Were. Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press.

Hanner Nordstrand, Charlotta et al. 2015, Kyrkans föremål. Beskrivande lexikon. Svenska kyrkan / Göteborgs universitet.

Immonen, Visa & Heini Kirjavainen 2016, Piispansauvan mysteeri. Pohjoinen reformaatio. Turku Centre for Medieval and Early Modern Studies & Turun historiallinen yhdistys, 97–102.

Immonen, Visa 2011, Heritageisation as a material process: The bishop’s crosier of Turku Cathedral, Finland. International Journal of Heritage Studies 18:2, 2012, 144–159.

Jacobs, Uwe Kai 2018, Amtssymbolik: Pannisellus am Abts-, Äbtissin- und Bischofsstab. Erbe und Auftrag. Benediktinische Monatschrift vol. 94 (2018), 210–214.

Kirjavainen, Heini 2015, Dress of a Saint? A Medieval Textile Find from Åbo Cathedral. Mirator 16:2/2015, 324–336.

Klockars, Birgit 1960, Biskop Hemming av Åbo. Helsingfors: Svenska litteratursällskapet.

Lundén, Tryggve 1955, Sankt Hemmings ikonografi. Finskt museum 1955, 71–78.

Räsänen, Elina 2009, Ruumiillinen esine, materiaalinen suku: Tutkimus Pyhä Anna itse kolmantena -aiheisista keskiajan puuveistoksista Suomessa. Helsinki: Suomen muinaismuistoyhdistys.

Schaefer, Gustav & Daniel Hummel 1947, Das Vorbild des Baselstabes. Archives héraldiques suisses/Schweizer-archiv für heraldik/Archivio araldico svizzero, 1947 A° LXI N° III–IV, 81–86.