Text and photos: Johanna Hohenthal

The government of Rafael Correa (2007-2017) pushed modernization of the education system in Ecuador through the establishment of large millennium schools at the expense of small rural schools [1, 2]. In the province of Pastaza, the government did not close upper secondary schools, but the reform hit hardest to the primary school students whose school journeys became longer due to closing down of community schools. In March, the research team visited the Shuar territory where three primary schools had been closed and several others had barely avoided the closure thanks to community resistance.

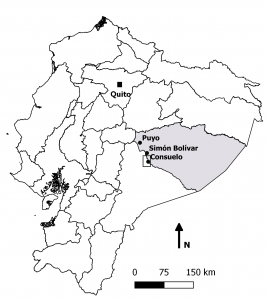

At the Jua Sharupi school in Consuelo, near the border of the province Morona Santiago, we met a teacher and a community member who told us about the process of school closings. According to them, the government officials made the decisions on which schools to close based on two criteria: the distance between the schools and the number of students in the schools. Especially, the first criterion was problematic because the distances were often measured as direct distances between the coordinate points on the map without considering the actual accessibility of the schools. For the students who lived in the remote forested areas, far away from the roads, the closure of small community schools would have meant hours of walking in a hilly terrain and crossing the rivers each day or, alternatively, leaving their communities and moving closer to the new school.

In several places, the local community resisted the intentions to close the schools and even took the officials to the forest to walk the routes to demonstrate the difficulties the new school journeys would bring to children. Thanks to this, some schools were spared. In 2016, the government attempted to close Jua Sharupi because of plans to establish a larger millennium school in the village of Chuwitayo, two kilometers away. At that time, Jua Sharupi had only five students while the limit in the intercultural bilingual education system was 15-20. The community resistance against the state authorities was strong. Eventually, the community invited children from a nearby village in Morona Santiago, which did not have its own school, to come to Jua Sharupi, so that they would have enough students. This invitation was successful and now the school operates independently with its own teachers, and is no longer under threat of closure.

We also visited the ruins of some of the closed schools. One of them, Iijinti (nuestra camino (Span.), our way (Eng.)), had been opened in 2007 with the help of foreign volunteers. The school was initially established because the closest school, two kilometers away in Chuwitayo, did not offer intercultural bilingual education. A woman who lived next to the school told us that the government closed the school in 2014 and promised to organize transportation so that the students could go to larger schools in Chuwitayo, Pitirishka (distance over 10 km) and even in Simón Bolívar (distance over 20 km). However, still today, there are no school buses or even local buses, only some long-distance buses that do not always stop to pick up the students. Therefore, sometimes the students cannot go to school at all. The closure of Iijinti was problematic especially for the smallest children who cannot travel long distances with or without a bus unless they have somebody who guides them. Recently, the community has begun the negotiations with the district officers and they are now collecting the resources to reopen the school.

Another school that we visited was called San Antonio, and it had been closed for a few months but operated now as an extension of the Tsantsa school in Pitirishka. We met the only teacher of the school, who found the extension arrangement quite difficult, because of daily traveling between the two locations, while carrying, for example, snacks to the students.

Finally, we also visited a school where a new millennium-style building had been built to the school compound. The idea had been to gather students from a wide area to this school. The school even had a pretentious name “Arutam” that refers to the powerful spirit of the Shuar people. However, the school had failed to attract enough students and it was closed. Unfortunately, we did not meet any local people to ask their thoughts about this school.

The small community schools are important for the intercultural bilingual education of the Ecuadorian nationalities. Close proximity in terms of physical distance and interaction between the community and the school are one of the quality criteria of education for the indigenous peoples. Therefore, the intentions of the new government to reopen some of the closed schools is a crucial step towards enhancing the intercultural bilingual education system in Ecuador.

[1] Arana, S. (2015). ¿Por qué se levantan las comunidades indígenas? La Línea de Fuego, agosto 25, 2015 [https://lalineadefuego.info/2015/08/25/por-que-se-levantan-las-comunidades-indigenas-por-silvia-arana/]

[2] Samaniego, S. (2016). Ecuador’s Intercultural Bilingual Education: Value Creating Pedagogy as a Tool for the Negotiation between Western and Andean world visions. In: The 12th Annual Soka Education Conference 2016, Soka University of America, Aliso Viejo, California, February 13th – 14th, 2016.