In the postpositivist academia of today, it is generally acknowledged that science is unavoidably subjective and biased, and objectivity and neutrality are rather seen as sacred but unattainable ideals. Science is hence recognised as a social process. Given its essentially human nature, science is also an inherently emotional process. In this post, I’ll discuss emotional integrity (the ability to recognise, accept, analyse and process one’s emotions) and acceptance of fallibility as an important personal skillset for scholars – and humans in general.

As demonstrated in the Facebook group Reviewer 2 Must Be Stopped!, scholars from all fields express a range of emotions: for example, anger, frustration and despair over mean and unreasonable reviews, as well as joy and relief over good feedback, published articles or granted funding. Emotions in academia are kind of self-evident – ask any scholar if they’ve ever been angry or excited while conducting research and you’ll get a ‘yes’.

Emotions in academia have been discussed and researched to some degree: for example, in the context of mental health and emotional labour in academia, in the wake of Tim Hunt’s comments about ‘emotional women’ in the lab, or in the context of the neoliberal academia of today. Emotions and academia are thus mostly discussed in the context of a (potentially) problematic situation to be critically addressed and solved.

Yet, emotions are also present in normal, everyday academia; in the research process and in scholars’ professional development. This aspect of emotions in academia is, however, rarely discussed, albeit with some exceptions, like Charlotte Bloch’s interesting study of the ‘culture of emotion’ in (Danish) academia. Nonetheless, a scholar’s tools for processing difficult personal emotions like uncertainty, anger, sadness, disappointment and envy, in particular, are rarely discussed in more detail. They are certainly not commonly discussed and taught at universities as a part of academic-professional education, not necessarily even in fields where the expert’s ability to process their own emotions can literally be a matter of life and death for someone, like in medicine.

While the ideal of the dispassionate, data- and fact-driven scientist still lingers, many scholars are passionate about and emotionally invested in their work. Everything related to their research is thereby also transformed into an issue about them personally, and research can indeed be emotionally taxing. All scholars face situations where they deliver poor-quality research and get harshly critiqued for it; have absolutely no idea what they are supposed to make of their data; receive rejection letters for articles and grant applications; lose their dream job to a dear colleague, and so forth. In short, scholars deal with professional failure and rejection that can feel deeply personal.

I argue that reflecting on one’s own fallibility and developing one’s emotional integrity can help in overcoming and learning from these situations. The pursuit of knowledge is the most essential task of a scholar, and failing at this task is a blow to a scholar’s professional identity and dignity. However, mistakes are also an inevitable part of research, and infallibility complexes and fear of failure can hamper one’s intellectual integrity (especially if they aren’t recognised). It is difficult to accept one’s own fallibility – nobody likes to be wrong, bad or rejected. Yet, I argue that it is important to try to detach fallibility from self-worth, both as a scholar and a human being. In other words, it is important to acknowledge that mistakes and failures, or admitting them to others, do not render you less worthy or respectable as a person. On the contrary; it is a part of professional and personal development.

Everyone has their own emotional patterns and mechanisms, and I of course cannot give a one-size-fits-all guideline for emotional integrity, particularly since it is and always will be an ongoing process. But I’ll share some thoughts and realisations that help me deal with some of the emotional challenges in academia.

Negative feedback. Let’s face it: it sucks, and it feels horrible. The hardest part for me is to accept the negative emotions that are unavoidably evoked by critique, as well as the feeling of being personally attacked. My immediate coping mechanism would be to rationalise my emotions away so that I don’t have to actually feel them. However, this leaves a lingering feeling of emotional dishonesty, which makes me both emotionally and intellectually constipated. So instead, I try to allow myself to feel angry, humiliated, frustrated, sad and desperate, and I console myself with the thought that they are, indeed, just emotions. They will eventually fade, and then I’ll be emotionally and intellectually better capable of analysing the feedback in order to take in the constructive and useful bits and to rise above unfounded criticism.

Rejection. This is by far the hardest pill to swallow. At best, it’s basically really negative feedback, like a rejection from a journal or conference. Feel the emotions; improve your work; try again. At worst, rejection is blunt and final: no justifications for the rejection (i.e., feedback for improving your work), and no possibility to appeal. Funding and job rejections are the absolute worst, since they basically mean that you are denied an opportunity to support yourself with your expertise. It is demoralising, especially when rejections start to pile up. Unfortunately, I don’t have a good recipe for dealing with these situations emotionally. I was unemployed for almost a year, and I felt like I’d hit a brick wall both professionally and personally. The only solution I have to offer is: get funded/employed. ‘Ha-ha’.

Competition. Dealing with funding/job rejections is particularly difficult when you are rivalled by people you know. It is hard to witness the success of others when you are left with nothing. However, for me, this is easier to handle than the rejection itself, albeit not easy. I again try to refrain from rationalising my feelings away. Instead, I try to accept, firstly, that I feel envious of others’ success, humiliated that I lost to them and angry that I’m being treated unfairly (which isn’t necessarily true). Secondly, I try to accept that I’m feeling horribly guilty for being envious or angry instead of being genuinely happy for my colleagues. Again, I try to remember that these are just emotions – I, as a person, am more than my emotions in a particular situation. I can choose to not express them, but can instead just congratulate my colleagues. Nonetheless, there’s no denying that losing to someone you know (instead of anonymous rivals) also makes your own loss somehow more tangible, which adds to a deteriorating sense of self-worth caused by recurring rejection. It is really hard.

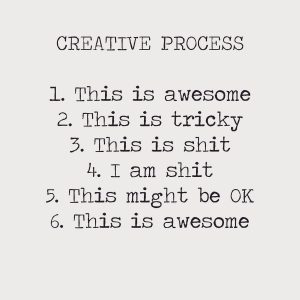

Uncertainty. While scientific research isn’t necessarily perceived as a particularly creative field, my research projects certainly follow this process.

Being aware of this cycle is my consolation when I am tormented by anxiety and crippling self-doubt in phases three and four. This, too, shall pass. By now, I know to anticipate the stage when I am utterly overwhelmed by my material which yet again has turned out to be nothing I expected, forces me to rethink my entire research strategy, makes me question whether I’ll ever have anything analytically meaningful to say about my material, drives me to read another fifteen articles and books on my topic, makes me question whether I’ll ever have anything meaningful to say about anything, pushes me to consider leaving academia altogether, etc. Until I eventually get to the following phases, be it through a triumphant eureka moment or painstaking and laborious trial and error – and I can again discern some kind of future for myself and my research. It is a part of the process. It will be okay, and I will be okay.

I want to re-emphasise that the above are a few examples of my own processes and mechanisms for addressing and processing difficult emotions in my own everyday academic life. They might help someone with similar emotional patterns, or then not. Nonetheless, I hope that this post can, for its part, contribute to demystifying emotions in the seemingly rational world of academia. All scholars feel emotions related to their work and professional development; many experience very powerful emotions, indeed. It does hence not serve anything to pretend that personal emotions and failure aren’t an integral part of academic work, or to try and explain them away. At worst, poorly processed negative emotions find an unproductive outlet in the form of harsh and unfounded critique towards others or oneself, or other forms of intellectual dishonesty towards oneself or one’s peers.

It is okay and normal to err, and it is okay and normal to feel.

Further reading

Askins, Kye & Blazek, Matej (2017) ‘Feeling our way: academia, emotions and a politics of care’, Social & Cultural Geography 18 (8): 1086–1105, DOI: 10.1080/14649365.2016.1240224

Bloch, Charlotte (2012) Passion and Paranoia: Emotions and the Culture of Emotion in Academia. Ashgate, Burlington.

Chhabra, Arnav (2018) ‘Mental health in academia is too often a forgotten footnote. That needs to change’, ScienceMag.org 19.4.2018, https://www.sciencemag.org/careers/2018/04/mental-health-academia-too-often-forgotten-footnote-needs-change

Feldman, Margeaux (2015) ‘“There’s no crying in academia,” Acknowledging emotional labour in the academy’, Gender & Society blog, https://gendersociety.wordpress.com/2015/10/27/theres-no-crying-in-academia-acknowledging-emotional-labour-in-the-academy/

O’Donnell, Karen (2015) ‘Why academia needs emotional, passionate women’, The Guardian 23.7.2015, https://www.theguardian.com/women-in-leadership/2015/jul/23/why-academia-needs-emotional-passionate-women

Woolston, Chris (2018) ‘Feeling overwhelmed by academia? You are not alone’, Nature 557: 129–131, https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-018-04998-1