Asylum seekers from Syria have prompted questions about integration recently, but historical sociolinguistics shows migration is not a new phenomenon and integration is possible.

Linguistic and ethnohistoric data indicate migration has played a large role in much of Europe’s history. Dr. Marijke van der Wal from Leiden University has been studying the effects of migration through language. Looking at these migrants’ language, we can get a glimpse of how they adjusted to their new homes.

Letters as Loot: where pirates save the day

“This time machine like collection of letters has value to discover more about migration patterns across Europe” – Dr. Marijke van der Wal.

During the Anglo‐Dutch Wars, English and Dutch pirates seized ships of enemy countries with government support. In order to prove these seizures as legal seizures of enemy ships, correspondence documents transported on the ships were provided as evidence. These letters are to this day held at the British Archives in England.

As most survived historical documents are from men of the upper class or clergy, these “letters as loot” provide invaluable knowledge on the everyday language of not just the upper but also the middle and lower classes of society. These letters, often correspondences between family members, also offer a peek into the lives of women and children.

Family letters from refugee merchants

Dr. van der Wal explains how authors were identified with the help of the Amsterdam marriage register

With so much movement of people from different countries, bilingualism, and even multilingualism, was a normal state of affairs, as it still is today.

Van der Wal presented the case of the merchant family Heusch who immigrated to Hamburg, Germany from the Netherlands in the 17th century to evade war and religious persecution. There, they became an important part of the German trade scene. Such successful integration does not mean complete assimilation. They still wrote to each other in their native language of Dutch with few influences of German present in their written language. Even second generation Heusch’s born and raised in Germany wrote in Dutch.

Turning back to the present day situation of migrant integration, it is then possible to envision a society where migrants become contributing members of society without the need to eliminate their native language and culture.

Population boomed in Amsterdam

Amsterdam’s population grew from 30,000 to 200,000 between 1585 and 1660 purely from an influx of migrant workers. Many of these migrants arrived in the Netherlands looking for better employment opportunities. Many locals were also concerned that the excellent system of poor relief in Amsterdam would attract more migrants. Does this sound familiar?

These migrants, however, were not leeches of the system but became fully integrated members of society. They often set up family in the Netherlands. Van der Wal suggests that one way of integrating is marriage, because “marrying a local woman was a fruitful strategy for integration and economic success.” Van der Wal has been surprised to find that some immigrants integrated into the Dutch society to the extent that they wrote letters in Dutch even to their non‐Dutch relatives.

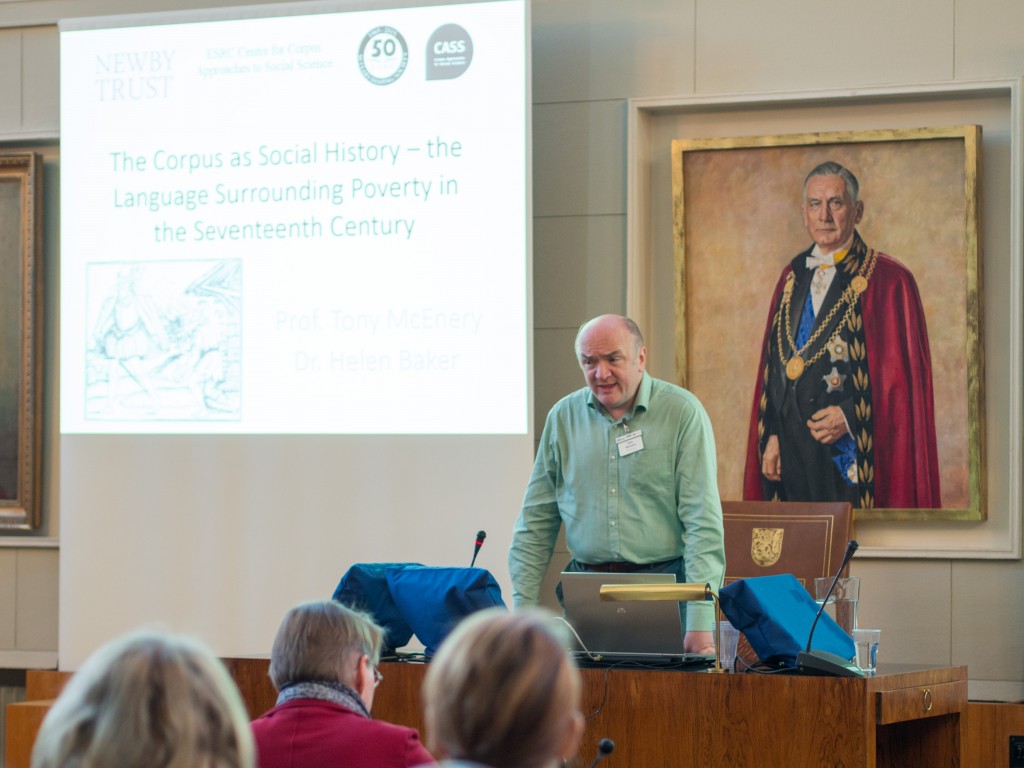

The HiSoN (Historical Sociolinguistics network) conference was held at the University of Helsinki, Finland from 10–11 March, 2016. Particular emphasis was placed on the social aspect of historical linguistics this year. Over 50 sociolinguists from 17 countries participated in this year’s conference, with over 20 languages represented in the papers. Dr. Marijke van der Wal opened this event with her plenary talk.

Text: Tina Lin, Anna Suutarla, Iida Hinkkanen. Photos: Anna Suutarla.

Read more

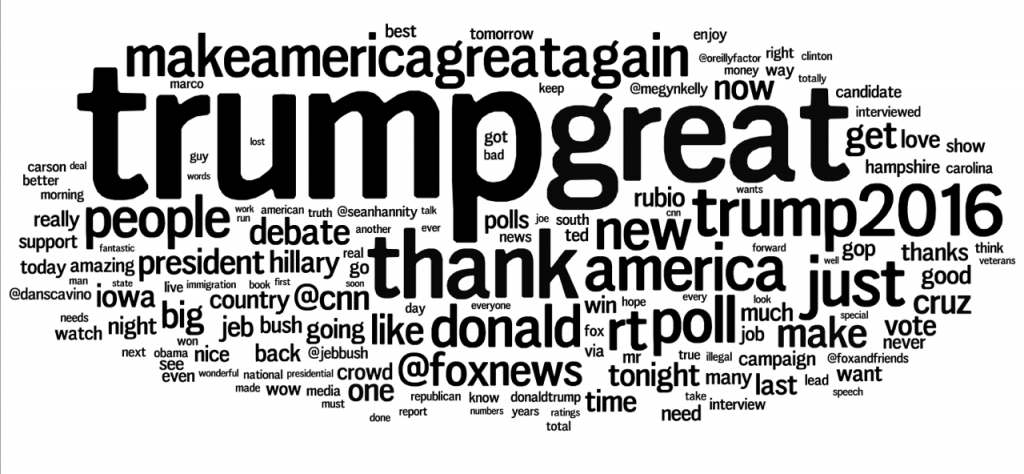

Another blog post from the HiSoN conference: ‘More Trump Than Is Healthy’ – How Political Speeches Have Changed